The land of Keftiu (Kftyw), or to the ancient Egyptians, the “Nail of the World”, is referred to by various names in the earliest written histories. To the early Hebrews, the people from the Island were Caphtorites (Hebrew: כַּפְתּוֹר, כַּפְתֹּר). Even as early as the 4th millennium BC, the people of Ugarit likely knew these Keftiu as the Caphtorim. At least one Assyrian text about Sargon the Great, the first ruler of the Akkadian Empire, refers to them as Kaptarû, or the Kaptarītum, around 2250 BCE. Still, though most experts now agree Crete was indeed Keftiu, the linkages and missing puzzle pieces of this magnificent civilization are only loosely manifold. The following report deals with biblical proof, historical records, religion, geography, and cultural aspects.

Biblical Fragments of Keftiu

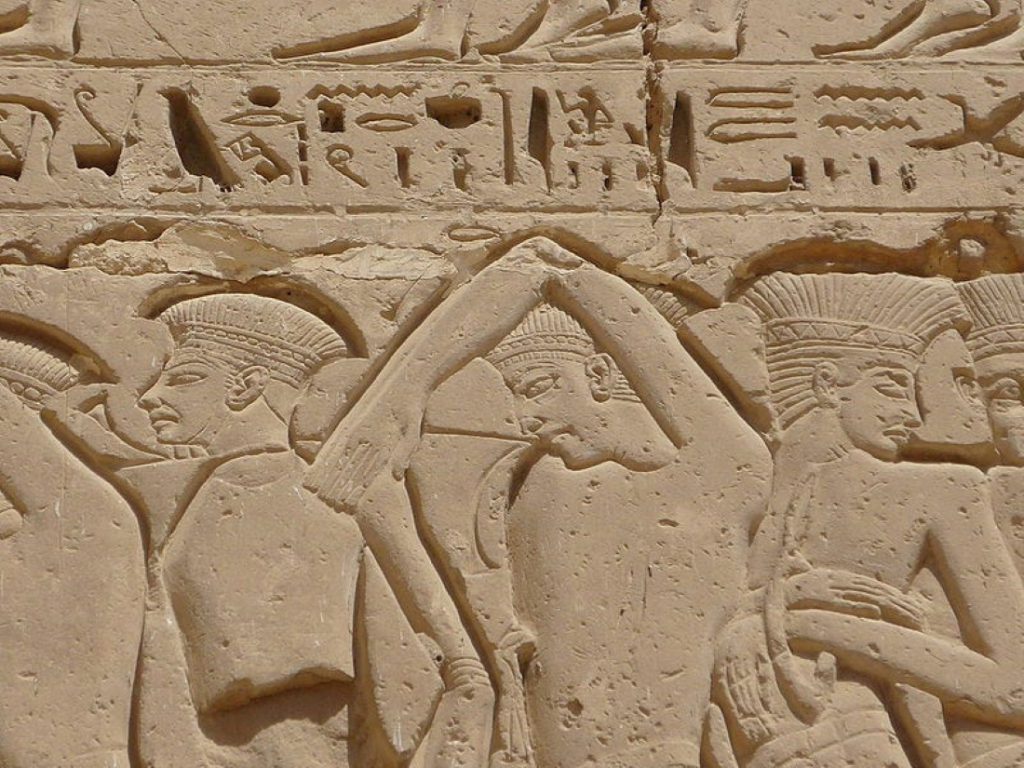

Biblical references highlight the Caphtor (Keftiu) connection to the Hebrews as the first homeland of the Philistines before they arrived in southern Palestine. According to Amos 9:7 and Jeremiah 47:4, the Philistines originated in Caphtor, while Deuteronomy 2:23 describes the Caphtorim driving out the Avvim near Gaza and seizing their lands. In Zephaniah 2:5, the scripts discuss the Philistines as a nation of the Cherethites, which almost certainly refers to Crete. Another pronunciation/association of this group is that the Kerethites are associated with archer warriors. Note that the Keftiu/Cretan archers were the most sought-after warriors before and for fighting in the Trojan War.

The line of religious research has resulted in volume after volume and is undoubtedly inappropriate to regurgitate here. However, some fascinating tidbits from Biblical texts/history may bear heavily on understanding who the Keftiu were and their reach. One such morsel is a reference to God’s “Judgement of Nations”:

Behold, I will stretch out My hand against the Philistines, even cut off the Cherethites and destroy the remnant of the seacoast. (Ezekiel 25:16)

The book of Ezekiel was supposedly written between 593 and 571 BCE, but there is a lot of confusion about which parts of these books were history and which were records of prophecies. Were these authors referring to the catastrophic Thera eruption and tsunamis (1620 BCE) that destroyed the Keftiu coasts and fleets? This theory seems worth investigating.

A point of interest here is the fact that the Philistines were already well established in Canaan in 2075 BC since Abraham (2100 BC and 1900 BC) and Sarah encountered Abimelech king of the Philistines in the city of Gerar. There’s also a Philistine-style helmet on the Phaistos Disk (above left).

Concerning Thera, the Book of Exodus (6th century BCE) and the Nile turning to blood have been associated with the volcanic ash from the volcano eruption. According to some scholars, the Exodus from Egypt occurred around 1476 BCE, but 144 years is a drop in the ocean of time and sketchy written histories. Many archaeologists once put the Thera catastrophe as late as 1500 BCE, so my reasoning is sound. If the suggestion here is valid, it also suggests that these Keftiu had a significant base of operations or satellite in Canaan. This is proven to an extent by the frescoes unearthed at the Canaanite palace at Tel Kabri (2,100–1,550 BCE) in Israel. (see further reference below)

Caphtor in Historical and Mythological Records

In ancient Assyrian documents, relying on earlier Babylonian traditions, Keftiu and Caphtor are associated with Kaptara, or the lands “beyond the upper sea,” or west of the Syrian coastline. Evidence from the Mari texts includes references to Kaptarû and Kaptarītum, names used in association with finer luxury goods thought to come from the Aegean. Additionally, Ugaritic texts reveal that Kōthar (also spelt Kōsar), a craftsman god, resided in Caphtor, further cementing its cultural significance. Given the Keftiu economy/trade was mainly in unparalleled crafted items like shoes, swords, ceramics, jewelry, fabrics, and so forth, the mention of this Kōsar further draws closer focus as to who these people were, and what their role/power in the ancient world was. The king of Ugarit wrote to King Zimri-Lim at Mari in Mesopotamia in 1750 B.C. asking to see his famous painted palace (Keftiu frescoes).

I find it fascinating that if you “Google” this supposed Keftiu god, what the algorithms turn up first is the Palaikastro Kouros, which is one of the world’s most mysterious and finely crafted works of art in the world. This fabulous statue was destroyed (it is thought) also around 1450 BCE. It’s intriguing the similarity 0between the Keftiu god and the Egyptian deity with the same purpose, Ptah (at right).

Moving our timeline slightly backwards, we find Kaptar mentioned in the Mari Tablets in an inscription dating to 1780-1760 BCE. The text is meaningful, mainly because it speaks of a man from Kaptar/Keftiu receiving tin from Mari.

I should reiterate here the level of craftsmanship/trade that made the Keftiu rich. The Island of Crete is nearly devoid of the natural resources needed for fine metalworking, but they were probably the ancient world’s finest metallurgists. Other ancient texts mention the Keftiu, who exported fabric and ceramics as far as Mesopotamia is concerned. As far as cultural and societal interplay, this report shows heavy evidence of the reach of this civilization coined as “Minoan” by Sir Arthur Evans.

Egyptian Texts and the Keftiu Connection

Egyptian records from the second millennium BCE also shed light on Caphtor. References to Keftiu (Kftyw) describe a distant maritime region reachable by ship. Artefacts and inscriptions, particularly those from Thutmosis III’s reign, depict men from Keftiu presenting goods to the Egyptian pharaoh. This portrayal reaffirms Caphtor’s active role in trade networks linking Crete, Egypt, and the Levant. The stone base of a statue during the reign of Amenhotep III is inscribed with the name kftı͗w in a list of Mediterranean ship stops prior to arriving at several Cretan cities such as Kydonia, Phaistos, and Amnisos. Given the order of the ports mentioned and that these voyagers referred to the port of kftı͗w, it seems possible that the capital of this first thalassocracy may not have been Knossos.

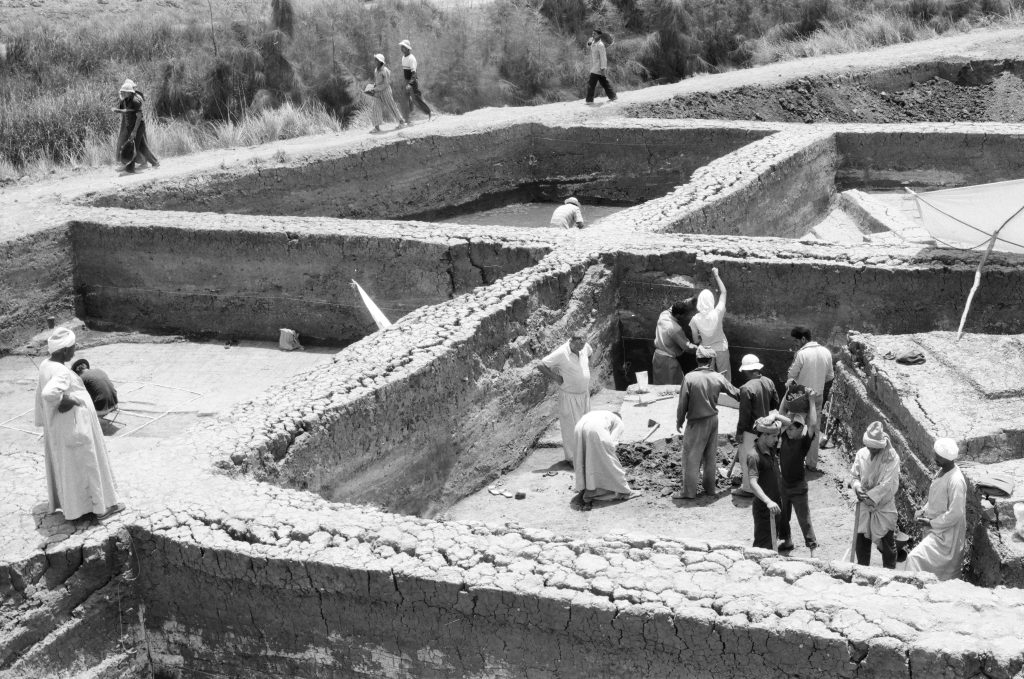

The question arises, “Which large port would Egyptian sailors visit before present-day Chania? The distinguished archaeologist Diamantis Panagiotopoulos has done extensive work in piecing together the origins of the Keftiu. His “Islands of the Winds” exhibition was, by far, the most telling archaeological presentation suggesting Keftiu’s thalassocracy I am aware of. In our conversations we often discuss the importance of the shipyards at Kommos on the Gulf of Mesara, as well as still undiscovered cities in the South and West of Crete.

In the paper “Was There Ever a ‘Minoan’ Princess on the Egyptian Court,” Uroš Matić mentions Sir Arthur Evans’ association of the ceremonial axe of the first king of the 18th dynasty Ahmose, as a sign of artistic exchange between Egypt and the Aegean cultures. This axe and Keftiu (Minoan) frescoes in Egypt are cultural puzzle pieces that suggest a union of the royal courts of Egypt and Keftiu. Furthermore, The gryphon depicted with the title’ mistress of the banks of the Haw nbwt’ insinuates (Eduard Meyer”, an alliance between the Egyptian royal family and Crete (Queen Ahmose?). This line of inquiry is, again, a subject for much greater study. New studies of Keftiu frescoes in Egypt also bring the princess theory into sharp focus. However, not even the great J.D.S. Pendleberry (my hero) would attempt to connect Knossos and Amarna so aggressively. And the connections to Akenahten and Neferteri, I have already gone out on a limb over before.

In another paper, “A Matter of Times”, Tiziano Fantuzzi makes an interesting assertion about the earliest connections between Keftiu and the Egyptians he wrote in 2013:

“From an archaeological point of view, the term is firstly attested only by the XVIIIth Dynasty. but it must have had a much earlier origin…”

The researcher cites evidence of Keftiu-Egyptian interconnectivity even as far back as Neolithic times, which seems the absolute era of Keftiu origins. Fantuzzi makes a case that this interrelationship existed, at least in the latter part of the third millennium B.C.

Cultural and Geographical Debates

To this day, scholars differ on the exact location of Caphtor. Many believe it refers to ancient Crete and nearby islands, supported by the Biblical texts I have mentioned. Archaeological studies, as I have also mentioned, reveal that Crete, a hub of Keftiu (Minoan) civilization, maintained extensive trade relationships with Egypt, Syria, and Mesopotamia during the second millennium BCE.

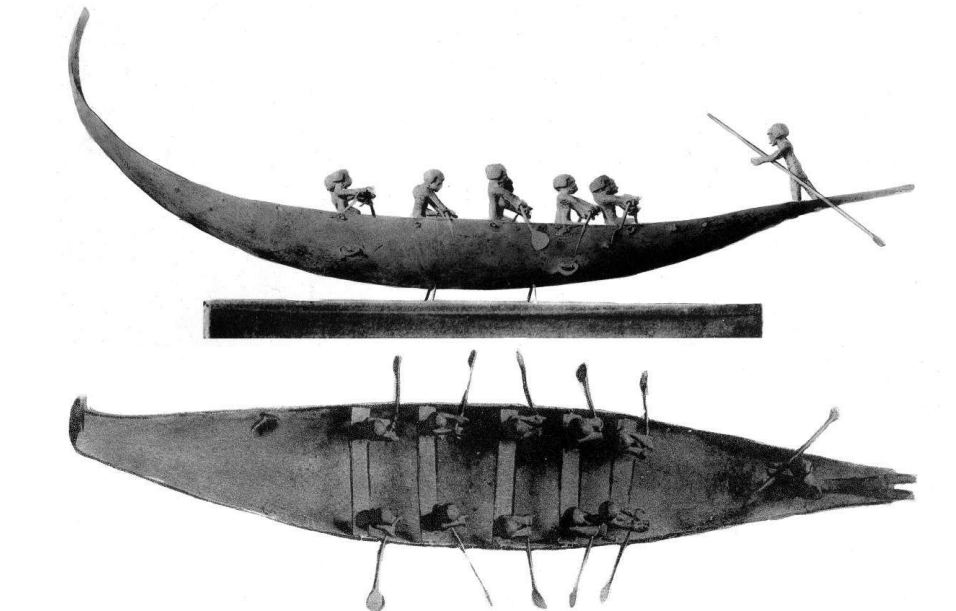

Others argue that Caphtor could be located along the southern coast of Asia Minor, near Cilicia, but these references were probably to Keftiu colonies or outposts. An interesting theory is that the name Caphtor may survive in “Karpathos,” an island off the Northeast shore of Crete. The Athenian historian and general Thucydides said that the mythological (?) King Minos was the first to organize a navy, and his civilization controlled vast regions of the Mediterranean and the Cycladic islands and basically ruled the seas. There is also evidence that the Keftiu may have helped expel the Hyksos (1650–1550 BCE). Here, the date seems significant if we recall the Thera disaster. Keftiu frescoes, I’ll mention later on, have also been theorized to be a “consequence of a dynastic marriage; of a ‘Minoan’ princess present on the Hyksos court.” (Uroš Matić citing Bietak) Further evidence of a Keftiu influence was an exquisite silver model of a Keftiu ship (presumably) found in the tomb of Ahhotep I.

I hope the narrow window of these dates from millennia ago strikes the reader the way they do me. Also, consider the Keftiu frescoes that are still being studied. Tell el-Dabca dated to the reign of Thutmose I (or Late Minoan IA-IB, according to Manfred Bietak). Here I must quote from Uroš Matić’s paper with regard to the Keftiu/Egypt linkage and the geography some still are at odds with:

Later, some even suggested that ‘Minoans’ left the islands they inhabited after the eruption of Thera and slowly but surely migrated into the Egyptian delta, before which they had already painted palaces in Miletus, Alalakh, and Tel Kabri.

Finally, Matić concludes in his paper on (basically) the Keftiu-Egyptian royal marriage that the frescoes that once adorned the throne rooms of Egyptian rulers were not necessarily proof there was a princess in the royal court of Egypt. However, he points out that the cultural heritage and sharing of ideas, beliefs, and art connects Keftiu and Egypt inextricably. I would say the connection was greater than with early Europeans, which is what Arthur Evans elucidated. In fact, the Keftiu had very little in common with the people’s Northward of Santorini, and they bore a remarkable likeness to their neighbors in the near East. But this is a topic for further discussion.

Additional photo credits: Statue of the Egyptian god Ptan, Margaret Lucy Patterson.