I never thought to question the so-called ‘Harvester vase’ from Ayia Triada. Excavated in 1902, the preserved upper half of the serpentine rhyton with relief decoration was first published by Robert Carr Bosanquet (1902: 389), who saw a ‘harvest-home festival’ being enacted by the 27 figures who surround the vase. Arthur Evans echoed this reading, calling it a ‘harvester’s dance,’ and ‘reapers’ rout’ (Evans 1928: 47), and John Forsdyke (1954) sealed its modern interpretation as ‘The “Harvester” Vase of Hagia Triada.’ Bobby Koehl elaborates on the harvest theme, seeing ‘a procession of youths setting out to harvest the community’s olive trees, perhaps under the supervision of a priest’ (2006:90), and Fritz Blakolmer (2007) further elaborates on the religious nature of the scene in relation to other processions evident in Minoan Neopalatial art, even hinting at the leader’s supreme status (2018: 44; 2019:74).

As one raised in the world of peace-loving Minoans, I accepted the ‘happy harvesters’ reading unquestioningly, despite the fact that the 21 uniformed male figures are clearly marching and saluting in a decidedly disciplined manner, and the other relief-decorated stone rhyton and cup associated with it in the Villa Reale are clearly linked to male athletic training and competition (Koehl 2006: 164–6), and perhaps even achieving military rank as the culmination of a rite of passage (Koehl 1986; 1997; 2016). It was upon reading Dieter Rumpel’s (2007) thoughtful re-evaluation of Luigi Savignioni’s (1903) original report that I began to reconsider the accepted interpretation. Savignioni’s suggestion that the 21 uniformed and saluting figures were marching in a military parade following a commanding officer dressed in a protective cuirass holding his staff of authority suddenly made perfect sense to me in the light of how I view events in Crete and the Aegean in the aftermath of the Thera eruption (MacGillivray 2009; 2013). So, in Bobby’s honour, I review briefly the elements represented on the vase and reconsider Savignioni’s original interpretation of the triumphal procession of mariners returning from a successful foray.

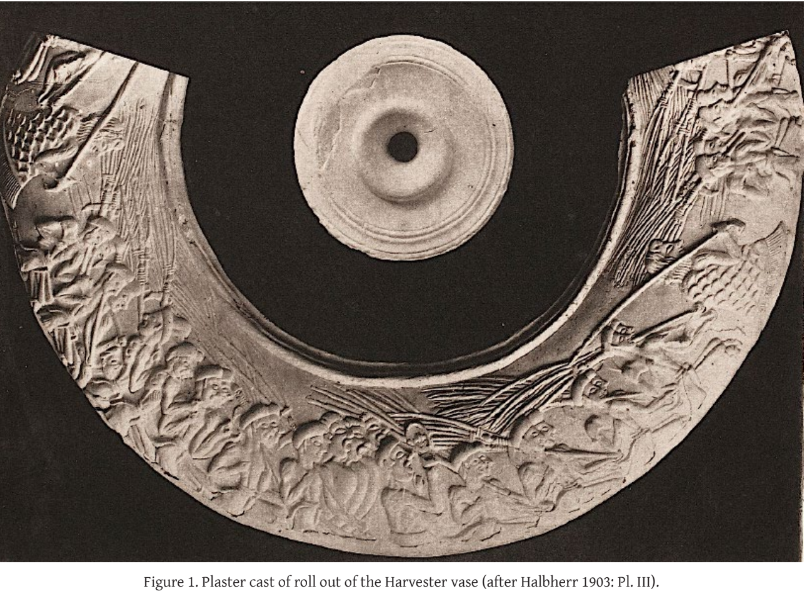

The Vase (Figure 1)

Federico Halbherr and his team found the upper half of the ovoid serpentinite rhyton in three joining fragments in Room 4 of Ayia Triada’s Villa Reale in 1902 (Halbherr 1903; Savignioni 1903; Banti, et al. 1977: 72; Koehl 2006: 90). The fact that it was broken and the lower half missing suggests that it likely fell from an upper floor at the time of the building’s violent destruction and conflagration, perhaps by earthquake (Monaco and Tortorici 2003), during the LM IB period, though it may have been smashed intentionally prior to that (Rehak 1994).

Found in adjacent Room 4a, and so likely stored on the first floor with the vase, were a bronze hammer, razor, ring, chisel, two sledgehammers, and the head of a hafted tool (Watrous 1984: 126 Table). Also likely fallen from the first floor were fragments of the so-called ‘Boxer’ rhyton, whose seven fragments representing less than a third of the vase were recovered in Portico 11 and the nearby Piazzale Superiore, which would have been accessed directly from the first floor of the Villa Reale (Halbherr 1905: 240; Banti et al. 1977: 83–5, 201; Koehl 2006: 164–5). Perhaps also fallen into nearby Room 13 was part of an alabaster boat and a magnificent rendering of a Dolium shell in Lipari obsidian (Evans 1928: 823 Pl. XXXI, b). Adjacent Room 14 was decorated on three sides with very high-quality frescoes depicting women in ritual poses on two walls and a Nilotic-style feline hunting scene on the third, perhaps indicating a shrine for women here on the ground floor (Militello 1998; 2001). The third vase relevant to our discussion here is the so-called ‘Chieftain Cup,’ recovered in fragments in the surface layers over the Southwest quarter, perhaps also likely from the upper floor (Banti et al. 1977, Koehl 1986). The South-West quarter also produced a concentration of daggers, spearheads and javelins in the destruction level (La Rosa and Militello 1999). All three relief-decorated stone vases must be considered together with the other finds believed to be stored in the villa at the time of its destruction. The latter include archives of 147 Linear A tablets and fragments, numerous inscribed roundels, and nearly a thousand sealings, all of which indicate the presence of scribes on both floors taking inventory of what Watrous believes is the heart of an agricultural estate (Watrous 1984). If so, this was a very wealthy estate indeed, considering the lavish use of gypsum revetments throughout the building, the imported Egyptian vases (Pendlebury 1930: 9; Warren 1995), and especially the nearly 500 kilograms of copper in ingots and the storage facilities. These ingots, the archives, the open paved courts and stepped ‘theatral areas’ (Cucuzza 2011), the shrine in Room 14, and the ritual vases likely stored in large ceremonial halls on the first floor (Banti et al. 1977: 60), which had direct access to the Piazzale Superiore, elevate the building, in my view, from a rural estate to a small LM I palace, like those at Gournia, Petras, and Kato Zakros, which likely functioned as ritual and administrative centers for their surrounding communities. And, like Gournia, Petras, and Kato Zakros, the Villa Reale faced the nearby sea, as Halbherr believed and called the well-paved road on its north side the rampa dal mare.

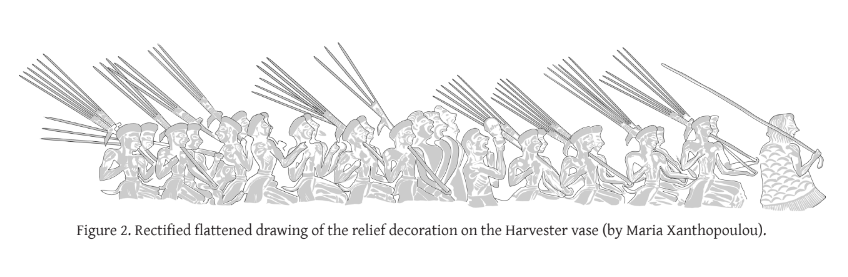

Iconography (Figure 2)

The relief decoration encircling the vase horizontally depicts a procession of 27 figures moving to the right. The leader is followed by eight marching youths then a sistrum player, a ‘chorus’ of three, and the remaining thirteen marching youths, with a fallen figure toward the end.

The Leader

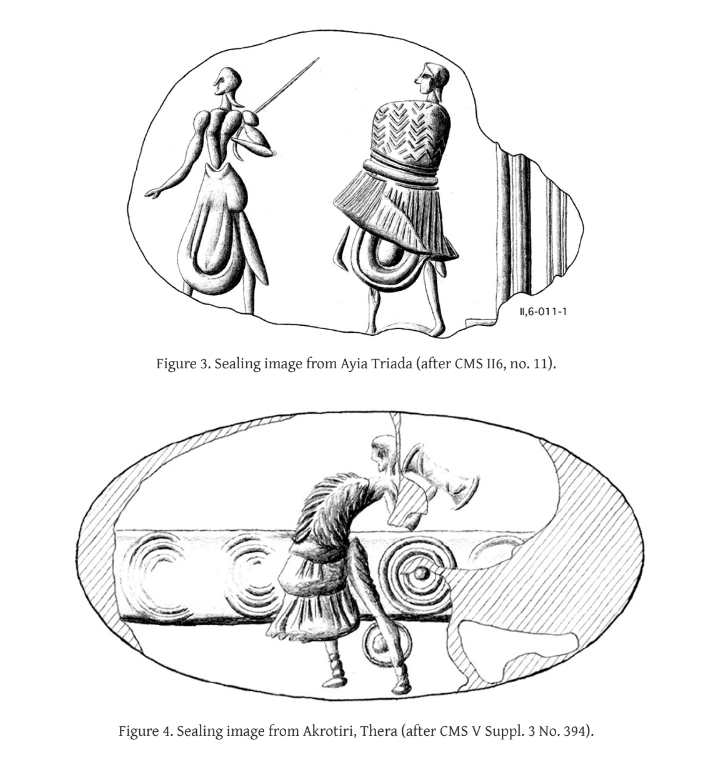

The figure leading the procession is an elderly man, to judge from his long flowing locks and mature facial features. He wears a fringed garment made of overlapping fish-like scales, first interpreted as a cuirass, a protective suit of plate armour (Savignioni 1903; Evans 1921: 435 n.1). His right arm is bent at the elbow so that the pointed staff with bent tip he clutches in his right hand is supported on his right shoulder. His left hand is not visible and his legs are missing. The most numerous sealings with identical impressions from the Villa Reale destruction depict two barefoot males in procession, the first carrying a very similar bent staff on his shoulder while the second follows with a fringed garment

similar to that of the leader on the vase (Figure 3). As both figures on the sealings wear the hide skirt evident also in a number of scenes from seals and metal rings (Blakolmer 2018), the leader on the vase is often restored barefoot with a similar hide skirt. Similar fringed garments with relief patterns are also closely linked to the Minoan double-bitted axe standard (Figure 4), for which at least seven stone bases were found in the destroyed Villa Reale (Evans 1921: 435 Fig. 312). The procession’s leader, therefore, can be identified by his maturity, bent staff, fringed scale-patterned cuirass, and likely hide skirt. The bent staff and relief patterned garment are featured together on the figure of deceased Syrian King Immeya depicted seated at a funerary ritual in his honour carved in relief on a hippopotamus ivory talisman from the Middle Bronze Age Tomb of the Lord of Goats at Ebla (Polcaro 2015; Jones 2019: 268 Fig. 9.26). The bent staff he holds in his right hand is very much a signifier of royal status in Syria (Polcaro 2015: 180 Fig. 9d). A similar staff but with back-curved crook is combined with a throne in Linear A sign AB 61 (Godart and Olivier 1985: xxxviii), the likely forerunner to Linear B sign *61 that Evans dubbed the ‘Throne and Sceptre’ and linked to his concept of the Priest-king (Evans 1921: 625–6 Fig. 464; 1936: 686–8 Fig. 670).

Palaima points out that any staff that is used to support someone is essentially a scepter, from the Greek verb σκηπτω: to prop up, hence σκυπτρον: a staff or stick to lean upon (Palaima 1995, 135). In Homer, it was borne by chiefs and passed on from father to son (Iliad 2).

In ancient Egypt, ‘The use of the staff varied from serving as a walking aid for the elderly, a baton for disciplining by the police, a military weapon, an agricultural tool for farmers herding livestock, a ceremonial implement carried by priests during religious rituals, and as a form of insignia, to outwardly express a person’s social and economic standing in society’ (Brown 2017: 189). The back curved crook we see in the Cretan scripts is very much like Egyptian hieroglyph S38, the Heka sceptre from which the verb to rule comes (Gardiner 1957: 508). This is the sceptre held by Osiris and Pharaoh to denote divine authority. The bent staff that our leader holds is closer to the Egyptian Awut (A’oot) staff, hieroglyph S39, the tool of the shepherd and emblem of leadership (Gardiner 1957: 509). So, our leader’s staff likely indicates his leadership role as the head of a group, but not necessarily the sovereign authority that the Heka staff, evident in Cretan Hieroglyphic/Pictographic script sign 059, would.

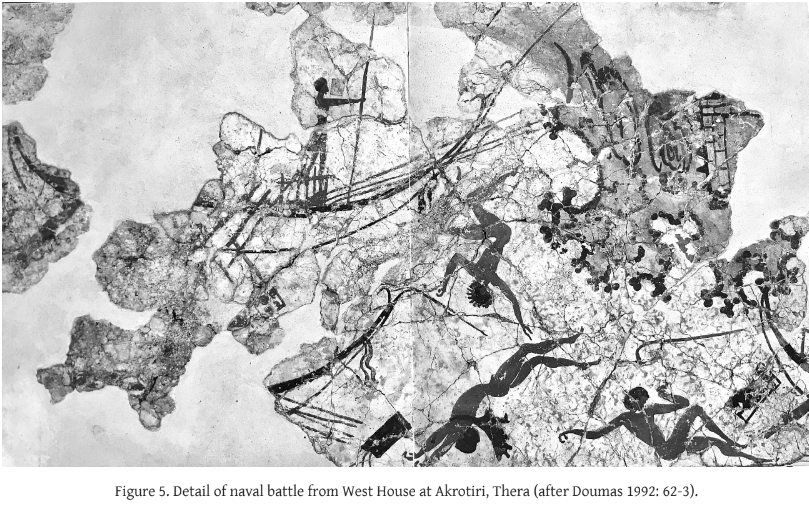

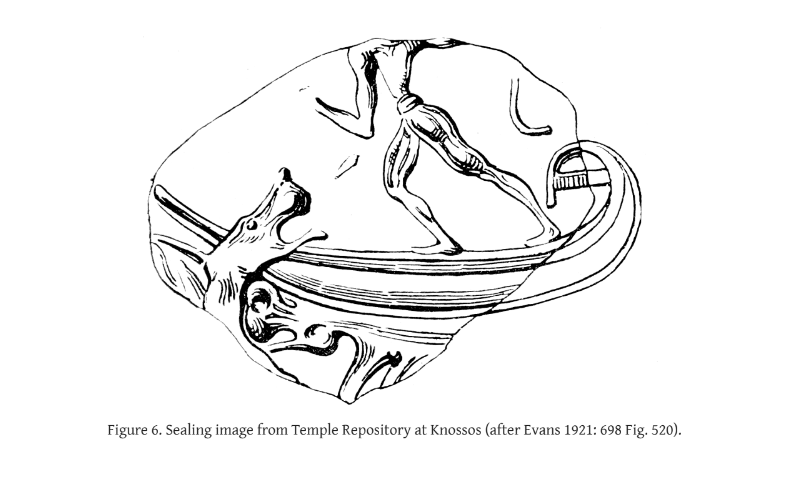

The Awut staff appears floating in the sea near the drowning figures in the apparent naval battle and/or siege in the miniature frieze from the West House at Akrotiri (Figure 5) (Doumas 1992: 62–3). Morgan sees it as a boat-hook, which, of course could be one of its functions (Morgan 1988: 153). But I believe that in this instance the artist may be signalling the importance of this particular sea battle in which someone in a high position, like the leader on our vase, was vanquished, thus making it even more memorable. And it could help identify the remains of a similar device evident in the seal impression from Knossos in which we see a vibrant male on the deck of a small craft with bent stern confronting a sea monster (Figure 6) (Evans 1921: 698 Fig. 520). The male here could be wielding the Awut staff, of which only the bent top is preserved.

The fringed garment depicted in numerous scenes on seals and rings being worn or carried by men has been dubbed the ‘Sacred garment’ (Blakolmer 2010: 93). Savignioni’s first impression was that this represents a protective cuirass composed of overlapping metal plates. The plates could just as well be leather and function very much like the cuirass entombed with Tutankhamun, which would have deflected projectiles while enhancing pharaoh’s appearance (Reeves 1990). Given the numerous depictions, this was a very important garment occasionally worn over the hide skirt (Figure 3). These fringed garments display a wide variety of relief patterns, which must have given particular distinction to the bearer. The pattern on our leader’s cuirass is most reminiscent of the one worn by Egyptian maritime god Nun in numerous depictions with its clear reference to fish scales (Wilkinson 2003:117). This scale-patterned cuirass and the Awut staff in the naval battle scene could indicate a maritime capacity for our leader.

Though not preserved, the leader most likely wore the hide skirt depicted on numerous seals and rings of this period, and also worn by both male and female officiates in the likely funerary ritual depicted on the later Ayia Triadha sarcophagus. These may be likened to the leopard skins worn by Sem priests in Egyptian funerary ritual and so could identify their Cretan bearers as members of a specific priesthood, perhaps linked to eschatological ritual, as in Egypt. They are always depicted barefoot in Crete and so may have been the leader shown here.

The Sistrum Player

The 21 marching youths, discussed below, follow the leader in two groups separated by a sistrum player and three other figures, all with exaggerated facial expressions and large lips. In the sistrum player, Pendlebury saw ‘a thick-set man in a skull-cap, rattling a sistrum, who looks remarkably like an Egyptian priest’ (1939: 213), and Breasted saw, ‘an Egyptian priest, with upraised sistrum,’ leading singing Cretan youths in a festal procession. (1948: 338 Fig. 127). Their reasons for this are three-fold. His close-fitting skull-cap with ears exposed is exactly like the one worn by the Memphite creator god Ptah, patron of craftsmen, in particular, but also anyone who creates, including musicians, who often wore the characteristic blue skull-cap of the Ptah priests in homage (Wilkinson 2003: 123–6). He appears to wear the wrap around skirt, or kilt, fastened at the front worn by Egyptian men of all ranks (Green 2001:275), but not enough survives to know if it had the more elaborate apron at the front, which would elevate his status somewhat (Zelenkova 2010). We can’t know if he is a priest, or simple musician, but given the importance of the scene, I am inclined to go with Pendlebury and Breasted.

The sistrum itself was an ancient Egyptian musical rattle ‘used in the divine cult, in religious processions, and in funerary cults’ (Manniche 2001: 292). The sound produced by rattling the metal disks on transverse bars was thought to resemble that of a papyrus stem being shaken, hence the handle usually resembles the papyrus stem. The arched loop on the type shown here designates it as a shm or ib (Ibid.: 293). The papyrus association is directly linked to the myths of creator goddess Hathor who, as a life-giving cow, emerges from a papyrus thicket, which is also where Isis raises her son Horus. Hathor’s many roles included overseeing procreation, so her officials often used sistra in temple ceremonies to promote masculine virility and sexual prowess (Manniche 2010: 14). She was also linked with intoxication and joyous festivals as ‘lady music,’ but also as goddess of the afterlife (Wilkinson 2003: 143). The latter could be why her sistra are found in tombs, e.g., the fine gilt wood and bronze examples found with Tutankhamun (Manniche 1976: 5–6). This notion may have been borrowed in early palatial Crete where sistra appear as symbolic clay copies in Minoan burials at Archanes (Sakellarakis and Sapouna-Sakellaraki 1997:351–6) Krasi (Marinatos 1929: 122 Fig.15), and Hagios Charalambos (Betancourt and Muhly 2006). But there are also two functional bronze examples from LM IB contexts. The one at Mochlos was found in perfect condition in a ‘Merchant’s Hoard’ of bronze tools and copper ingots (Soles 2011). The discovery of this first functional bronze loop sistrum allowed Tom Brogan to recognize the second one, the so-called head of a hafted tool found in Room 4a at Ayia Triada and so perhaps stored with our vase (Brogan 2012). Brogan even speculates that the Ayia Triada sistrum could be the one immortalised on the vase and that both were part of the rituals performed there.

The Chorus

Behind the sistrum player to the far side, three figures with curly, combed, or braided pulled-back hair and large lips wear cloaks or curved, irregular shields and sing, chant, or scream with exaggerated wide-eyed and wide-mouthed facial expressions. Evans saw ‘girl choristers’ here (1928: 47 Fig. 22), and they are considered in discussions of gender in Minoan art (e.g., Larsen 2011), but the sideburns clearly evident on the nearest one suffice to identify all three as males. The cloaks, or shields, are often likened to those born by the three figures on the reverse of the ‘Chieftain cup’, commonly seen as large hides destined to make shields (Koehl 1986; Blakolmer 2010: 107). But in this case the legs are visible so what they wear, or hold only covers the upper body. The hair on these three figures is unusual in Crete, but reminds us of the curly hair shown on two male heads in fresco fragments from Knossos (Cameron and Hood 1967: Pl. VI Figs. 8–9; Hood 1978: 69 Fig. 52 E). Curly hair and large lips may identify them as Africans. They could be captives protesting loudly with their arms tied back, soldiers with oddly shaped shields encouraging the troop, or singers in heavy robes accompanying the sistrum player. I prefer the third option and call them the chorus here.

The Twenty-one Marchers

The two groups of marching youths are very similarly attired in round flattish beret-like flat cap and outfitted in the well-known belted loin cloth with penis sheath, dubbed the Minoan zoma (Sapouna-Sakellaraki 1971), with a long tapering blunt device secured to the left thigh, but there are interesting differences. The first group following the leader comprises four well-ordered pairs with torso shown in 3/4 view marching forward briskly, as the fluttering leather or cloth back flap on their zomas indicate, with left leg raised in an orderly lock-step formation. Each holds their three-pronged implement in their extended left hand so it rests on their left shoulder with right arm bent and fist clenched with extended thumb at the chest. The second group that follows the sistrum player and chorus is less well-ordered. There is a single youth with implement in the lead followed by a pair marching very much like the first four pairs with their implements held high and clasping their right fist to the chest, all shown with torso in 3/4 view. These are followed by two pairs marching in lock-step like the others but without implements and with both fists raised. The first pair of these are shown with torso in 3/4 view, but the nearest one of the second pair is shown in profile and instead of holding his clenched right fist to his chest, he extends it forward to strike the face of the youth in front of him. Next comes a pair whose closest youth to the viewer, with torso shown in profile, is distracted by another youth, perhaps smaller and younger, who either trips and falls against his backside, or clutches him from behind with his right arm on his thigh. Both have open mouths as though speaking or shouting at each other. The smaller youth interrupts the next pair in procession by knocking up the innermost of two’s left arm so that his implement points straight back. The final pair march in perfect order like first pairs and thus restore protocol.

The side of the vase with the senior leader is quite orderly, even stately, while the other side with sistrum player is filled with drama: wide open singing, shouting, chanting or even screaming mouths, a punch in the face, and a smaller figure tripping against, or clinging to another while upsetting the one behind him. Was this vase meant to be seen as a continuous procession, or was there a side meant to be viewed by one group while another saw something quite different, perhaps even on separate occasions, one sombre and one joyful?

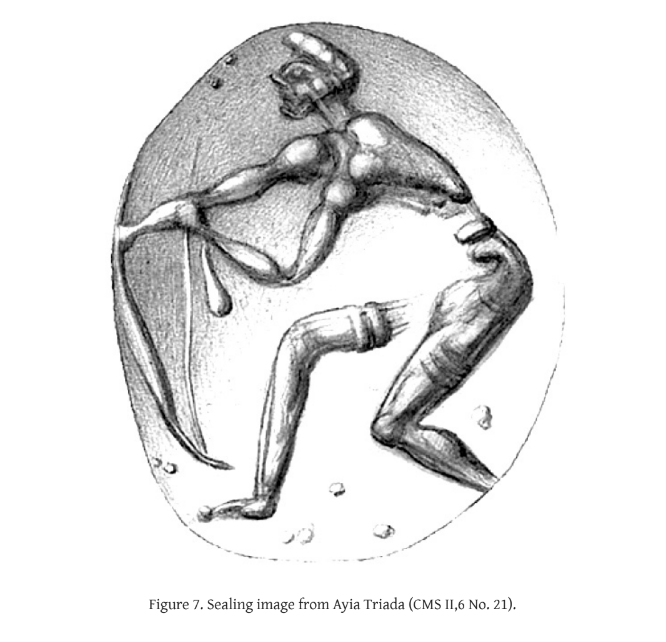

The round flat cap is identical on each of the 21 marching youths and quite characteristic, though it also appears on a terracotta head from Phaistos (Pernier 1935: Pl. XV), and on an archer in one of the Ayia Triada sealings (Figure 7). This may also be what we see on the heads of many youths in the flotilla fresco from the West House at Akrotiri in Thera, but, as these are black, we cannot distinguish between a cap and a close-cropped head (Figure 5). One would expect these caps to be felt or cloth and designed to keep the wearer’s head warm, as they lack the long flowing locks typical of men in other Minoan works of this period, e.g., the Boxer rhyton and Chieftain Cup, unless their proud locks are gathered up in these caps during their service, for which, however, we see no evidence, no loose strands.

The trident implement that 17 of the 21 sport on their left shoulders looks a combination of two things. The lower part resembles a battle axe with pointed slightly hooked bronze axe head slotted into the hefty wooden handle whose top is tightly secured with twine to hold it in place. This tool is further supplemented with three long thin very pointy staves secured onto the top of the axe with more twine. The axe on its own is designed to be swung in a chopping motion, but not the staves, which would break off easily if sideways pressured were applied. The only way these could be effective would be in a thrusting motion, the way pikes are used to keep an enemy at a distance in battle. I believe that we are seeing something like this implement in action in the same sea battle scene with the Awut staff of the vanquished leader from the West House at Akrotiri cited above (Figure 5). The same painting shows long pointed stakes in groups of three and four protruding from the two ships’ prows preserved, but also apparently between these two craft. These are not the paddles we see propelling the larger ships in the flotilla scene in the frieze on the South wall of the same room. For one thing, there are no oarsmen evident in the battle scene. I suggest that we are looking at long sharp staves, like the sailors’ pikes of more recent times used to attack enemy ships while closing in for boarding. The sharpened points fixed as long deadly tridents for thrusting into an enemy ship held by our marchers could have cut through the gunwale and forced opponents back then the axe head could have been used as a grappling hook to secure the craft prior to boarding. This action most likely would have been preceded by a volley of arrows from marines like the one pictured in Figure 7, if the flat cap can be taken to identify marines, as I propose here (Warming 2019).

The marching youths have a long blunt device strapped to their left leg, visible on all but two whose left legs are hidden so we may assume that all had them. Koehl sees these as folded cloths to spread out to catch the olives that would fall when these harvesters struck the laden branches with the long poles (2006: 90). If we reconsider the tridents as pikes, however, we may recognise these as batons, or mauls, shaped exactly like a well-known Egyptian tool, the fuller’s club, or hm, Gardiner’s hieroglyphic sign U36, a logogram for majesty, servant, or launderer (Gardiner 1957: 520). But the distinctive tapered club with narrow handgrip had other functions in Egypt, as we see one raised high by a fisherman as he sits on the prow of a reed boat preparing to club the catch he pulls aboard in a painted relief in the tomb of princess Idut in Saqqara (Wilkinson 2005: 82). A related tool, I believe, is the parrying or throw stick carried by the marching marines, also armed with battle axes and bows, who accompany the barque shrine of Amun across the Nile in the annual Opet Festival of renewal in Thebes immortalised on the walls of the chamber Hatshepsut commissioned for the barque atop her temple at Deir el Bahri (Lipińska 1974: 163–7; Roehrig 2005: 154 no.82). These reliefs may have been cut at the same time the Ayia Triada vase was crafted, when Minoans were in the Nile rebuilding their navy after the Thera eruption (MacGillivray 2009).

Our 21 marching youths, then, may be viewed as a troop of marines identified by their flat caps and equipped with battle axes enhanced with a fixed trident exclusively for thrusting to make way for boarding an enemy vessel. In close contact the trident could be removed and the marines would fight with the battle axe in their right hand and the parrying stick, or cudgel, in the left. Perhaps the latter is what we see attached to the left wrist of the archer/?marine from Ayia Triada in Figure 7. The troop shown here does not look battle-worn, but rather battle-ready. I propose that we are seeing commemorated on this precious rhyton a military parade of recently graduated marines with brand new weapons being led toward their ship. Their leader may have both the spiritual power of a high priest, and the secular power of a commander. The sistrum player could be a Hathor priest performing a ritual to both boost their virility while ensuring the safe journey of their immortal souls should they perish on their mission. The three cloaked figures with open mouths and hair pulled back must be part of the ceremony being performed by the sistrum player, and so could be a group of specialized temple singers reciting a song or

hymn that the observers and users of this vase could have been familiar with and perhaps even sang during the ritual this vase functioned in. The solemnity of the serious side of the vase is offset by a lively side brought to life by mischief, music and song.

Comment

My reading suggests that this vase should join its companion, the Chieftain cup, in commemorating a major stage in a young man’s career, what Ellen Davis and Bobby Koehl introduced into Aegean studies as the ‘Rites of Passage.’ It would fit well into Puglisi’s third sub-category of, ‘celebrating the access of an individual to small, closed and high-specialization groups such as secret societies, warrior classes, religious fraternities, criminal organisations and so on.’ (Puglisi 2020: 64). And it would cease to be the outlier in Wendy Logue’s classification of these vessels; I would move it from its isolation in Economic Imagery’ to the popular ‘Martial Imagery’ (Logue 2004), where Savignioni would have had it all along.

If Brogan’s speculation that the sistrum found with the vase is the one depicted upon it, we could suggest that the procession took place, perhaps annually with each graduating class, at Ayia Triada itself. And what better way to celebrate the annual graduating class of marines than in a public procession along the Rampa Dal Mare?

While Minoan Crete has no overt sovereign ruler iconography evident in great mural programs (Niemeier 1987: 90–1), there is plenty of imagery with prominent figures associated with recognised religious symbols. Blakolmer, following Bintliff (1977: 160–4) suggests that Minoan rulers exerted political power through the religious authority granted them at the highest priestly level so that Minoan religious symbols effectively functioned as political insignia (2019: 74). This would allow us to identify our leader as the high priest of a religion that employed the Awut staff, fringed cuirass, and double-bitted axe as their most prominent and distinctive symbols. His appearance here, with the Hathor priest, makes this a religious procession in which our graduating class of marines is not only being celebrated but consecrated in their task to defend the realm. If ever there were an image that embodies the Thalassocracy of Minos, this could be it.

Acknowledgement

It gives me great pleasure here to acknowledge how much I have learned from Bobby Koehl over the thirty-odd years we have known each other, from our days as vibrant youths at Knossos, through the amazing New York years with the Aegean Seminar, then the Palaikastro Kouros discussions and publication, to now. I offer him this unpopular reading of a very popular vase that he knows well, or so he thinks. I am encouraging him here to think again. My interest in this subject started in 1996 at Deir el-Bahari when I was struck by the similarities of the Egyptian procession of marines to the contemporary Minoan procession of harvesters. I knew something wasn’t right, and it’s taken me this long to figure it out.

Bibliography

Banti, L., F. Halbherr, and E. Stephani. 1977. Haghia Triada nel periodo tardo palaziale. Annuario della Scuola archeologia di Atene 55, n.s. 39, 1977.

Betancourt, P.P., and J. Muhly. 2006. The sistra from the Minoan burial cave at Hagios Charalambos, in E. Czerny, I. Hein, H. Hunger, D. Melman, and A. Schwab (eds), Timelines: Studies in Honor of Manfred Bietak, vol. 2: 429–35. Leuven: Peeters.

Bintliff, J.L. 1977. Natural Environment and Human Settlement in Prehistoric Greece, Oxford.

Blakolmer, F. 2007. Die ‘Schnittervase’ von Agia Triada. Zu Narrativität, Mimik und Prototypen in der minoischen Bildkunst. Creta Antica 8: 202–42.

Blakolmer, F. 2010. Small is beautiful. The significance of Aegean glyptic for the study of wall paintings, relief frescoes and minor relief arts, in W. Müller (ed.) Die Bedeutung der minoischen und mykenischen Glyptik: 91–108. Mainz.

Blakolmer, F. 2018. A “special procession” in Minoan seal images: Observations on ritual dress in Minoan Crete’ in P. Pavúk, V. Klontza-Jaklová and A. Harding (eds) ΕΥΔΑΙΜΩΝ. Studies in honour of Jan Bouzek: 29–50. Prague.

Blakolmer, F. 2019. No kings, no inscriptions, no historical events? Some thoughts on the iconography of rulership in Mycenaean Greece, in J. M. Kelder and W. J. I. Waal (eds) From ‘Lugal.gal’ to ‘Wanax’ Kingship and Political Organisation in the Late Bronze Age Aegean:

49–94. Leiden.

Bosanquet, R.C. and M.N. Tod. 1902. Archaeology in Greece 1901–1902. The Journal of Hellenic Studies 22: 378–394.

Breasted, J.H. 1948. A History of Egypt. New York.

Brogan, T. 2012. Harvesting an old rattle: The bronze sistrum from the “royal” villa at Hagia Triada, in E. Mantzourani, P.P. Betancourt (eds) Philistor: Studies in honor of Costis Davaras: 15–22. Philadelphia, PA:

Brown, N.R. 2017. Come my staff, I lean upon you: The use of staves in the ancient Egyptian afterlife. Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 53: 189–201.

Cameron, M. and S. Hood. 1967. Sir Arthur Evans’ Knossos Fresco Atlas. Farnborough.

Cucuzza, N. 2011. Minoan “Theatral Areas,” in 10th International Cretological Congress, vol. A2: 155–170. Khania.

Doumas, C. 1992. The Wall-paintings of Thera. Athens.

Evans, A.J. 1921. The Palace of Minos at Knossos, vol. 1. London.

Evans, A.J. 1928. The Palace of Minos at Knossos, vol. 2. London.

Evans, A.J. 1936. The Palace of Minos at Knossos, vol. 4. London.

Forsdyke, J. 1954. The “Harvester” Vase of Hagia Triada. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 17: 1–9.

Gardiner, A. 1957. Egyptian Grammar, vol. 3. Oxford.

Godart, L. and Olivier, J.-P. 1985. Recueil des inscriptions en lineaire A, vol. 5. Paris.

Green, L. 2001, Clothing and personal adornment, in D.B. Redford (ed.) The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, vol 1: 274–9. Oxford.

Halbherr, F. 1903. Resti dell’Eta Micenea: scoperti ad Haghia Triada presso Phaestos. Rapporto delle richere del 1902. Monumenti antichi 13: 5–74.

Halbherr, F. 1905. Scavi eseguiti dala Missione archeologica italiana ad Haghia Triada ed a Festo nell’anno 1904. Memorie della Reale Istituto Lombardo di scienze e lettere 21: 235–54.

Hood, S. 1978. The Arts in Prehistoric Greece. Harmondsworth.

Jones, B.R. 2019. Ariadne’s Threads. The Construction and Significance of Clothes in the Aegean Bronze Age. Leuven-Liege.

Koehl, R.B. 1986. The chieftain cup and a Minoan rite of passage. Journal of Hellenic Studies 106: 99–110.

Koehl, R.B. 1997. The villas of Ayia Triada and Nirou Chani and the origin of the Cretan Andreion, in R. Hagg (ed.) The Function of the Minoan Villa: 137–49. Athens.

Koehl, R.B. 2006. Aegean Bronze Age Rhyta. Philadelphia, PA. Koehl, R.B. 2016. Beyond the “Chieftain Cup”: More images relating to Minoan male ‘rites of passage,’ in

R.B. Koehl (ed.) Studies in Aegean Art and Culture. A New York Aegean Bronze Colloquium in Memory of E.N. Davis: 113–32. Philadelphia, PA.

La Rosa, E and P. Militello. 1999. Caccia, guerra, orituale? Considerazioni sulle armi minoiche da Festòs e Haghia Triada, in R. Laffineur (ed.) Polemos: 241–63: Liege.

Larsen, E. 2011. Deconstructing gender oppositions in the Minoan Harvester Vase and Hagia Triada Sarcophagus. Studia Antiqua 10: 37–47.

Lipińska, J. 1974. Studies on the reconstruction of the Hatshepsut temple at Deir el-Bahari – A collection of the temple fragments in the Egyptian Museum, Berlin, in Festschrift zum 150 Jährigen Bestehen des Berliner Ägyptischen Museums: 163–171, pls. 18–23. Berlin.

Logue, W. 2004. Set in stone: The role of relief carved stone vessels in Neopalatial Minoan elite propaganda. Annual of the British School at Athens 99: 149–172.

MacGillivray, J.A. 2009. Thera, Hatshepsut, and the Keftiu: Crisis and response in Egypt and the Aegean, in D. Warburton (ed.) Time’s Up! Dating the Minoan Eruption of Santorini: 148–64. PLACE: Publisher.

MacGillivray, J.A. 2013. Animated art of the Minoan Renaissance, in R.B. Koehl (ed.) Amilla: The Quest for Excellence. Studies Presented to Guenter Kopcke in Celebration of His 75th Birthday: 145–8. PLACE: Publisher

Manniche, L. 1976. Musical Instruments from the Tomb of Tut’ankhamūn, Oxford.

Manniche, L. 2001. Sistrum, in D.B. Redford (ed.) The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, vol. 3: 292–3. Oxford.

Manniche, L. 2010. The cultic significance of the sistrum in the Amarna Period, in A. Woods, A. McFarlane and S. Binder (eds) Egyptian Culture and Society. Studies

in Honour of Naguib Kanawati, vol 2: 13–26. PLACE: Publisher.

Marinatos, S. 1929. ‘Προτομωïκòς θολωτòς τáφος παρà τò χωρíον Κρáσι Πεδιáδος’ ArchDelt 12, 102–41.

Militello P. 1998, Haghia Triada I. Gli affreschi. Padova.

Militello P. 2001, Archeologia, iconografia e culto ad Haghia Triada in età TM I, in R. Laffineur -R. Hägg (eds), Potnia. Deities and Religion in the Aegean Bronze Age: 159–168. PLACE: Publisher.

Monaco, C. and L. Tortorici. 2003. Effects of earthquakes on the Minoan “Royal Villa” at Haghia Triada (Crete). Creta Antica 4: 409–16.

Morgan, L. 1988. The Miniature Wall Paintings of Thera. A Study in Aegean Culture and Iconography. Cambridge.

Niemeier, W.-D. 1987. Das Stuckrelief des “Prinzen mit der Federkrone” aus Knossos und minoische Götterdarstellungen. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archaeologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteilung 102: 65–98.

Palaima, T. 1995. The nature of the Mycenaean Wanax: Non-Indo-European origins and priestly functions, in P. Rehak (ed.) The Role of the Ruler in the Prehistoric Aegean: 119-39. Liege.

Pendlebury, J.D.S. 1930. Aegyptiaca. Cambridge.

Pendlebury, J.D.S. 1939. The Archaeology of Crete. London.

Pernier, L. 1935. Il palazzo minoico di Festos, vol. 1. Rome.

Polcaro, A. 2015. The bone talisman and the ideology of ancestors in Old Syrian Ebia: Tradition and innovation in the royal funerary ritual iconography, in P. Matthiae (ed.) Studia Eblaitica. Studies on the Archaeology, History, and Philology of Ancient Syria, vol.

1: 179–204.

Puglisi, D. 2020. Rites of passage in Minoan palatial Crete and their role in structuring a house society, in M. Relaki and J. Driessen (eds) OIKOS. Archaeological approaches to House Societies in the Bronze Age Aegean: 63–80. Louvain-la-Neuve.

Reeves, C.N. 1990. The Complete Tutankhamun. London.

Rehak, P. 1994. The ritual destruction of Minoan art? Archaeological News 19: 1–6.

Roehrig, C.H. 2005. Hatshepsut. From Queen to Pharaoh. New York.

Rumpel, D. 2007. The “Harvester” Vase revisited. Anistoriton Journal, InSitu, 10.3: 1–13.

Sakellarakis Y., Sapouna-Sakellaraki E., 1997. Archanes, Minoan Crete in a New Light, vols. 1–2. Athens.

Sapouna-Sakellaraki, E. 1971. Μινωϊκόν Ζώμα. Athens.

Savignioni, L. 1903. Il vaso di Haghia Triada. Monumenti antichi 13: 77–131.

Soles, J.S. 2011. The Mochlos sistrum and its origins, in P.P. Betancourt and S.C. Ferrence (eds) Metallurgy: Understanding How, Learning Why: 133–46. Philadelphia,

Watrous, L.V. 1984. Ayia Triada: A new perspective on the Minoan villa. American Journal of Archaeology 88: 123–34.

Warming, R.F. 2019. An introduction to hand-to-hand combat at sea–General characteristics and shipborne technologies from c. 1210 BCE to 1600 CE, in J. Rönnby (ed.) On War On Board. Archaeological and historical perspectives on early modern maritime violence and warfare: 99–124. Stockholm.

Warren, P.M. 1995. Minoan Crete and Pharaonic Egypt. Interconnections in the second millennium BC, in W.V. Davies and L. Schofield (eds) Egypt, the Aegean and the Levant: Interconnections in the second millennium BC: 1–18. London.

Wilkinson, R.H. 2003. The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Egypt. London.

Wilkinson, T. 2005. Dictionary of Ancient Egypt. London.

Zelenkova, L. 2010. The royal kilt in non-royal iconography?. The Bulletin of the Australian Centre for Egyptology 21: 141–66.

Editor’s note: This paper was originally titled “Reaper’s Rout or Mariner’s March? Reconsidering the ‘Harvester’ Vase from Ayia Triada.” The title was abbreviated for SEO purposes.