Summary. It is generally asserted that the representations of Aegeans in Theban private tombs cannot be regarded as a reliable historical source since the gift-bearers of this independent region were depicted by Egyptian artists as tributaries. The present paper is an attempt to test the validity of this orthodoxy from the Egyptological perspective. The new explanatory approach is based on a contextual analysis which embraces the entire body of foreigners’ processions in the Theban tomb-paintings. It is suggested that these scenes provide, within certain iconographical conventions, an accurate record of historical reality, thus offering a valuable insight into the mechanisms of pharaonic power. The question of the political vs. economic nature of the depicted activity, the diplomatic gift-giving, is taken up in an appendix at the end of the paper.

The Hard Evidence: Subject, Context, Perception

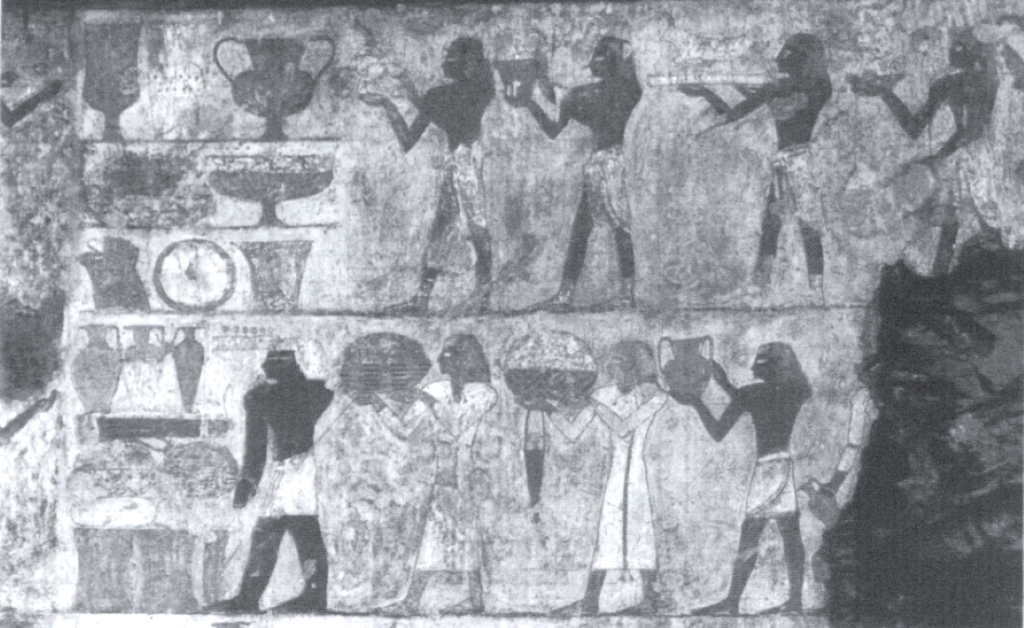

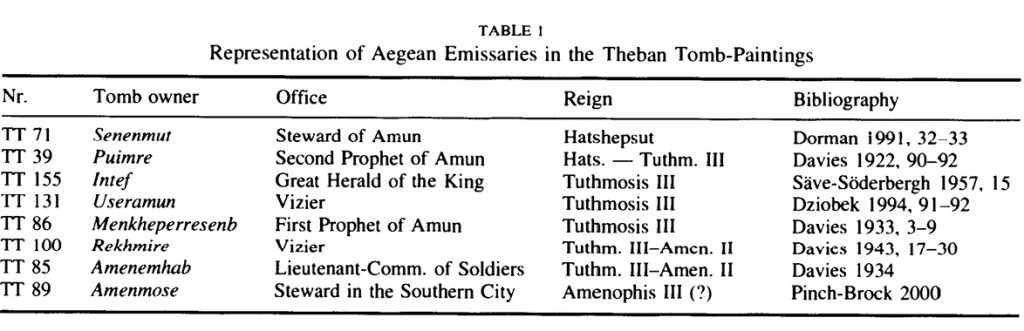

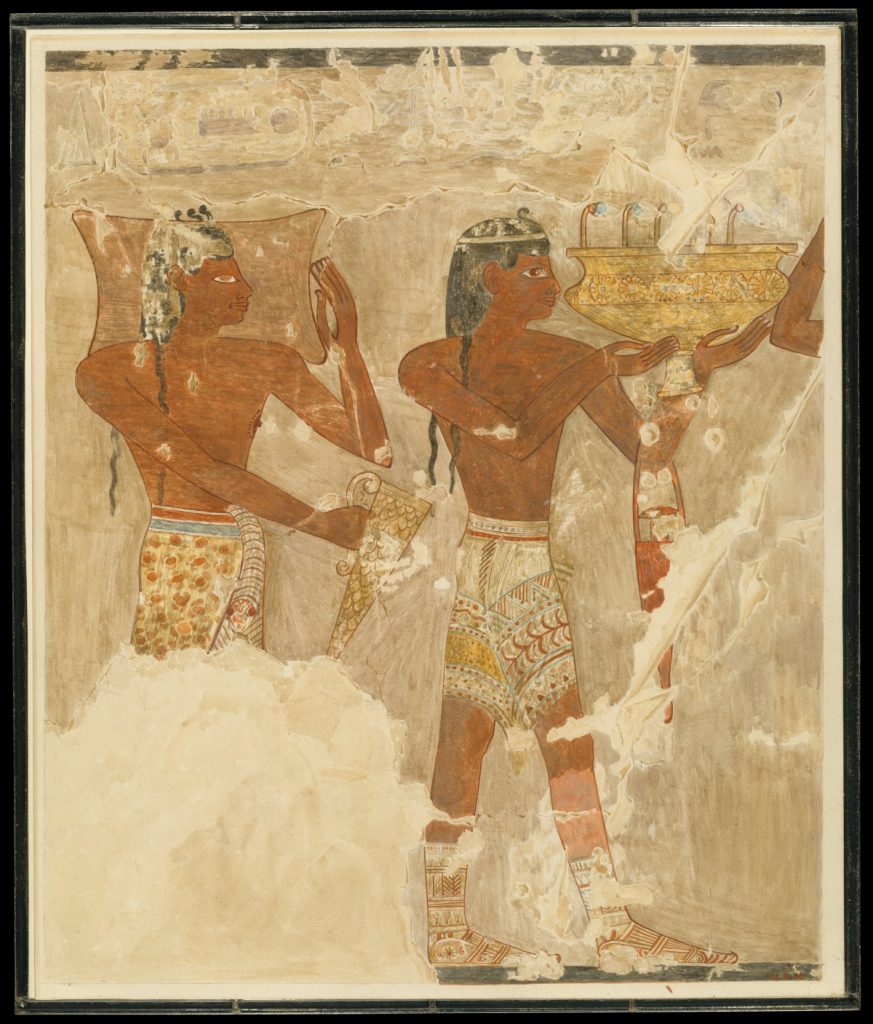

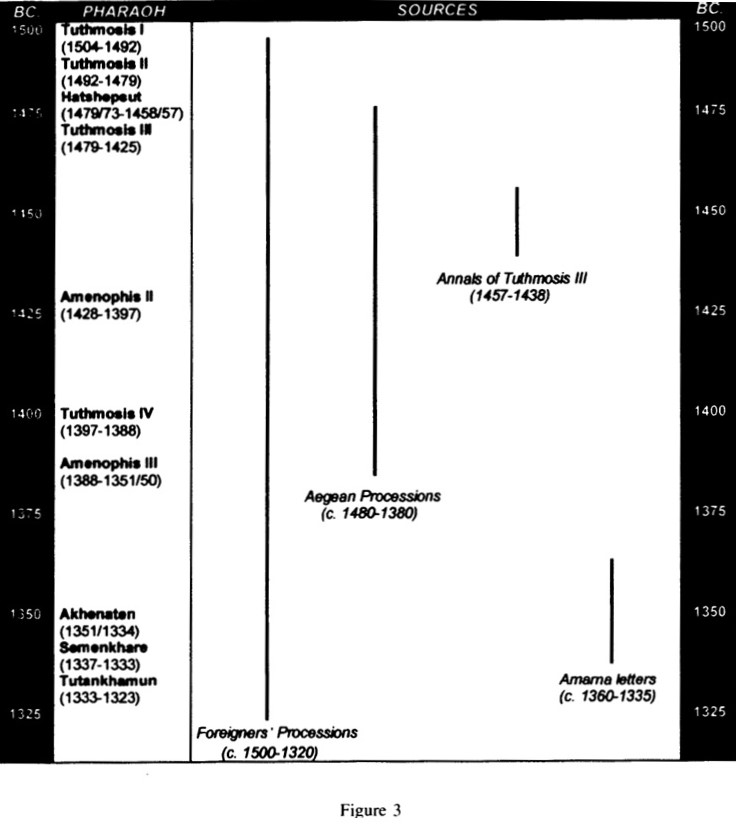

During the time of the 18th Dynasty, the representation of foreign embassies bringing valuable objects to the Egyptian king became a favourite theme in the pictorial programme of Theban private tombs. Eight of these monuments belonging to high officials of the Egyptian state feature, among other peoples, Aegean processions which consist exclusively of male emissaries (Figure 1). In the adjacent hieroglyphic inscriptions, the Aegeans are designated either as ‘Keftiu’, the Egyptian name for Crete, or as ‘people from the jw hrj-jb nw w3d-wr (the Isles in the Middle of the Great Green)’, almost certainly the Egyptian name for the Aegean islands, probably including the Peloponnese.[1] The career of these eight officials spanned the time from Hatshepsut through the early reign of Amenophis III, in terms of absolute chronology, a period of about 100 years between c. 1480 and 1380 BC (Table l).[2] Beyond this basic factual evidence, we are in the fortunate position to know how Egyptians perceived these pictures simply because they had labelled them. In the most extensive and interesting of the preserved inscriptions, that from the tomb of the vizier Rekhmire, we read:

“The coming in peace by Keftiu chiefs and the chiefs of the islands of the sea, humbly, bowing their heads down because of His Majesty’s might, the king Menkheperre (Tuthmosis III) Given life forever! When they heard his achievements in every foreign land, their jnw were on their backs, requesting the breath, wanting to be loyal to His Majesty, so that the might of His Majesty will protect them” {Urk. IV, 1098: 14 – 1099: 3; for the translation Galan 1995, 91).”

Retrospective

One century has now elapsed since the identification of Keftiu with Cretans (Hall 1901-02, 166; Vercoutter 1956, 33)[3] and at first glance, after this long period of intensive research, there seems to be little hope of contributing any original ideas on the subject.[4] In retrospect, it becomes evident, however, that while iconographical matters attracted all the scholarly attention, historical issues did not receive adequate treatment. Almost every single figure and object of these scenes has been thoroughly analysed, revealing how the Egyptian painters drew in some cases upon a direct experience of historical reality but in many others on stereotypical artistic conventions (Kantor 1947, 41^9; Furumark 1950, 223-239; Vercoutter 1956, 195-368; Wachsmann 1987, 4-26, esp. 6-9; Barber 1991, 330-338; Helck 1995, 50-62; Matthaus 1995; Rehak 1996; Rehak 1998; Manning 1999, 209-220). On the contrary, historical reconstruction seems to have halted at the level of early impressions, failing to consider improvements in our understanding of Egyptian sources and, to some extent, improvements in historical methods. Consequently, our historical perception of this evidence has hardly changed throughout the century. According to this, the Egyptian artists were driven either by propagandistic motives or by a sense of ethnic superiority and rendered the Aegean diplomatic gifts as the delivery of tribute, often placing the Aegeans among people who were in some way submissive to Egypt.

This one-sidedness of previous research is also the reason for rejecting the historical reliability of the scenes. The interpretation was based mostly on iconographical criteria, trying to draw historical conclusions from the artistic manner of the Egyptian painters.[5] Accuracy in the representation of emissaries and/or their valuable offerings was conceived as the single criterion for determining the historical value of these processions. A further and more serious shortcoming was the ‘insularity’ of this traditional approach, for the Keftiu paintings were always examined in isolation from the physical and intellectual context in which they were embedded.

There has been a single attempt to view this pictorial evidence in its Egyptian setting by Jean Vercoutter (1956, 188-189, 194) who tried to link the depictions of Aegean emissaries with the careers of the tomb owners. His starting point was the observation that the reception of the foreign ‘tribute’ formed one of the most prestigious official duties of the vizier. He came to the conclusion that the scenes in the tombs of the viziers Useramun and Rekhmire referred to real ceremonial events which marked an important moment in the life of the deceased.[6] Vercoutter’s approach was radically different from all other interpretive attempts before or after him in providing an alternative, Egyptological point of view. Yet, paradoxically, his position seems not to have been acknowledged in the field of Aegean archaeology since it never became a matter of debate.

Methodology

A new attempt at a contextual approach…

The present article again addresses the historical authenticity of these processions by taking up Vercoutter’s neglected argument and combining it with some recent results in Egyptological research. The main concern here will be to look not at the pictures but through them, trying not to examine the artistic manner of the Egyptian painters but to read the message they wanted to convey. To reach this goal, it will be necessary to extend Vercoutter’s perspective by examining these scenes not only in context but also in corpore, in other words, within the wider iconographical theme of foreigners’ processions in the Theban tombs. Hence, from this point onwards, we will be referring not to Aegeans but to foreigners, pursuing a comprehensive interpretation which will also be applicable for the Aegeans as part of this whole. In respect to methodology, this analysis follows what seems to be a logical path, proceeding from the level of the physical context (the location of the scenes), through the level of representation (their subject matter), to the level of historical reality (the actual historical meaning of the depicted events).

Redefining the subject…

It is necessary at this point to redefine our subject in its wider context. The foreign processions with valuable objects for the Egyptian king appear in 37 scenes from 27 different Theban tombs of high officials.[7] These representations display in their ideal, complete version the following elements:

- The foreigners, with their offerings, proceeding in one or more registers

- The prostration by the men heading the processions in front of the Egyptian ruler

- A display of valuable objects

- The scribes making lists of the items brought

- The tomb owner presenting the processions to the Pharaoh

- The Pharaoh enthroned at the far end of the scene[8]

There are two main iconographical variations of this theme, depending on the presence or absence of the Pharaoh as the recipient of the foreign gifts. In the first and most common type, the Pharaoh is present (Porter, Moss and Burney 1970, 463, Appendix A, l[b]).[9] In the second type, the Pharaoh is substituted by the high official and tomb owner (Figure 2)[10] who receives the foreign processions as a representative of his lord (Porter, Moss and Burney 1970, 464, Appendix A, 7[a]).

The two most frequently depicted ethnic groups are the Syro-Palestinians (24 examples) and the Nubians (11 examples); in both cases, people were politically subjugated by the Egyptian state. Foreigners from independent countries are clearly depicted less often: Keftiu or Aegeans in eight tombs, people of Punt in four, Hittites in two, and finally Mitanni in one.[11]

Interpretation

First level: The physical context

At the beginning of this interpretative attempt, it is essential to approach our subject from a wider perspective. In the royal iconography of the ancient Near Eastern empires the processions of foreigners with gifts or tribute for their overlord constituted a dominant theme. They demonstrated in a most explicit and vivid manner the king’s supremacy over foreign countries, claiming the leading position of his land abroad. These scenes decorated public buildings habitually located in the nation’s capital itself, the prominent centre of political power and consequently the most appropriate place for the creation and display of politically charged messages. The most imposing examples at our disposal come, obviously due to find circumstances, only from later periods: worth mentioning among these are the New Assyrian reliefs at Nimrud, Balawat and Khorsabad dating in the reigns of Assurnasirpal II, Shalmaneser III and Sargon II (Bar 1996, 69-208) as well as the Achaemenid reliefs, decorating the staircases of the Apadana building at Persepolis (Walser 1966).

Returning to the Egyptian material, we have to place its three basic external components (time, place and context) onto this diachronic and intercultural background. The components of time and place correspond with the Near Eastern historical picture. Chronologically, these scenes are restricted, apart from marginal exceptions,[12] to the time of Egypt’s imperialistic expansion to the north and south. This is the era between Tuthmosis I and Tutankhamun, a period of about 180 years between 1500 and 1320 BC, when the pharaonic state, driven by a combination of strategic and economic motives, annexed large territories in Syro-Palestine and Nubia (Kemp 1978; Weinstein 1981, 1-17; Redford 1992, 148-177). Geographically our scenes are concentrated — apart from isolated exceptions (LA IV, 765 n. 13) — in lone location, the capital of the 18th Dynasty, Thebes, again resembling the Near Eastern evidence. The third component however, the context, diverges from the historical pattern outlined above. These processions do not appear in temples or palaces as in the Near East[13] but in a private sphere, the tombs of high officials occupying a prominent place in the front hall, usually on the right or the left side of the entrance to the long corridor. In contrast to the inner, sacred part of the tomb, this front room had a secular character. Its entire textual and pictorial programme was dedicated to the everyday and professional life of the deceased, mostly documenting episodes from his political career, such as the participation in court ceremonies at the side of the Pharaoh or the successful exercise of his official tasks. As the compelling interpretation of Jan Assmann (1987, 212-213) has shown, this comprehensive self-representation served as a Botschaft (message) sent by the deceased to the various tomb visitors. Its primary aim was to perpetuate his memory, which would, in turn, guarantee him the regular exercise of the mortuary rites (Guksch 1994, 2).

Considered in this intellectual setting, the foreigners’ processions emerge as historical episodes, marking one important moment in the political career of the deceased. These episodes must have been official ceremonies of the Egyptian court in which the tomb owner played a prominent role, either by mediating between the Pharaoh and the foreign embassies or even substituting for his king. The atmosphere of these audiences is vividly illustrated in a model letter of the Papyrus Koller dating in the Ramesside period. Here, the Egyptian viceroy of Nubia writes to a subordinate official:

“Remember the day of bringing the jnw, when you pass into the Presence beneath the Window, the nobles in two rows in the presence of His Majesty (may he live, be prosperous, be healthy), the chiefs and envoys of every foreign land standing dazzled at seeing the mw” (Caminos 1954, 438-439, 5:1-3).”

The participation in ceremonies at the side of the Pharaoh was of paramount importance in the Egyptian court where social and political rank were defined by the proximity to the person of the king. As a consequence, the event itself and its depiction in the tomb must have constituted an impressive statement of high status. Returning to our main concern, the historicity of these scenes, we can view them as an objective testimony of the depicted events, since their main purpose was not state propaganda but the self-representation of the tomb owner.

We must clarify at this point in what temporal sense these pictures possessed a historical character. In most cases our scenes lack any indication of time and space. Only twice are we informed that the ceremonies took place on the occasion of the New Year Festival (Porter, Moss and Burney 1970, 7T86 [8] and 84 [5]; Davies 1933, 2-9 pi. 3-7; Urk. IV, 950, translated by Blumenthal et al. 1984, 349 no. 4) and, in another instance, that the location of the depicted event had been the royal palace at Heliopolis (Porter, Moss and Burney 1970, TT 84 [9]; Urk. IV, 951; translated by Blumenthal et al. 1984, 349-350 no. 1). The entire pictorial programme in the front hall of the tomb referred predominantly not to single actions but to episodes of a periodic, cyclic character in the life of the deceased. As a consequence, these biographical scenes must have been understood by the Egyptian audience not as a statement of a specific event but as a statement of a permanent function (Gaballa 1976, 65). It is thus possible that the tomb owner had participated more than once in these court ceremonies or, if not, that he wanted the tomb visitors to believe so, by omitting any indication of a concrete time and place.

Second level: Representation

We have seen so far that the physical context provides a sound argument for the documentary character of the scenes. Moving now to the level of representation, it is the nature of the ceremonial events which merits our special attention. The question which arises here is what the Egyptian artists really wanted to depict. The strongest argument against the historicity of these processions rests on the belief that independent peoples were represented as tribute bearers, thus indicating a clear distortion of historical reality. Only recently has it become apparent, however, that this consensus was founded on first impressions rather than on a careful critical analysis. In fact, when representatives from independent and subjugated countries appear together, neither the scenes nor their inscriptions provide any explicit evidence that they had indeed been depicted as tribute-bearers.

I shall start with the inscriptions. In the few cases where they are sufficiently preserved (seven in total) the objects carried by the foreigners are always described as jnxv, a word traditionally translated as ‘tribute’ (LA VI, 765; Boochs 1984; Kantor 1947, 41; Furumark 1950, 224; Vercoutter 1956, 130-135, 188-194; Wachsmann 1987, 32, 35, 49, 93-94). New evidence shows this translation, which derived exclusively from the use of the word in royal texts and iconography, to be inappropriate and arbitrary. A crucial step towards a better understanding of the word is to strip this term of its derogatory overtones and to concentrate on its etymology. The literal translation of jnw, a perfective passive participle of the verby’n/ (= to bring, fetch), is ‘that which is brought’ as it is clearly illustrated by its ideogram, the ‘legged bowl’ (Hannig 1995, 74; Goldwasser 1995, 21-22).[14] Beyond this general meaning, the word seems to have had a special connotation as gift rather than tribute, as Sir Alan Gardiner suggested more than fifty years ago (1947, 127). Much later, his opinion was strengthened in a series of articles by Renate Muller-Wollermann (1983; 1984) and Edward Bleiberg (1981; 1984). What seems to be the most convincing argument for the translation ‘gift’ is now provided by the work of Ben Haring (1997, 18, 47-51, 84, 183-185, 205-206, 249-250) who studies the administrative texts of New Kingdom temples, i.e. a much more reliable source than the phraseology of royal inscriptions. In this context jnw denoted additional/occasional contributions by the king to the temple, in other words a supplement to the regular income of the temple estates. It was conceived, according to Haring, as a token of the king’s concern for the material well-being of the temples (Haring 1997, 185) and in this function bore a close resemblance to the meaning of ‘gift’. Supporting evidence for this interpretation can be further provided by the lack in the Egyptian language of any special term denoting the diplomatic gift. Through a comparative reading of hieroglyphic and cuneiform documents the word jnw appears as the only possible equivalent of the Akkadian sulmanu (greeting gift), used in the royal correspondence of the Amarna archive to describe the gifts exchanged between foreign rulers (Liverani 1990a, 263; Bleiberg 1984, 158 n. 8).16

Apart from this fact, the inscriptions never claimed that the Aegeans were politically dependent on Egypt. The inscription in Rekhmire’s tomb (see above) explicitly mentions that the Aegeans came because they had ‘heard’ of Pharaoh’s achievements, not because they had been in any way affected by them. Jose Galan (1995, 92-93) is certainly correct when he notes that the verb sdm (= hear) in contrast to the verb m33 (= see) expresses in the context of foreign affairs an indirect knowledge, referring to countries “that never ‘suffered’ nor even ‘saw’ the king’s military actions”. The Aegeans came to recognise his status as lord of the conquered territory and not to prove their loyalty. What is traditionally translated as ‘loyal’ in the same inscription is actually a common Egyptian metaphor ([wn] hr mw [n]), which literally means ‘to be in the water of someone’ (Lorton 1974, 87-89). Perhaps we will never be able to understand the exact semantic range of this ‘hydraulic’ expression which could have meant a political, social or even economic form of relationship. This case illustrates how an argument in favour of the propagandistic character of this inscription rests not on what Egyptians actually thought but on what we think they thought.

The implications of the textual evidence are corroborated by the images. The objects carried by the dependent Syro-Palestinians and Nubians, the only potential suppliers of tribute, have for the most part the same precious and exotic character as the offerings of the independent people and, as Muller-Wollermann (1983, 87; LA VI, 765) convincingly argued, must be viewed equally as gifts. They indeed diverge clearly from the tribute deliveries of the same people, recorded in the Annals of Tuthmosis III and the letters of the Amarna archive, which consisted mainly of the basic agro-pastoral production or raw materials (Panagiotopoulos 2000, 147-150).[15] Besides this iconographical hint, there is another more complex line of reasoning supporting the gift-hypothesis. From the Amarna archive and other written sources of the 18th Dynasty it becomes apparent that in Egypt’s foreign relations a tribute in the strict sense of the word, i.e. a punitive political measure or a sign of submission, did not exist. A large part of Syro-Palestine and Nubia had been incorporated into the Egyptian administration system as provinces and paid taxes as the territories in Egypt proper (Panagiotopoulos 2000, 153-158).[16] This taxation was considered by the Egyptian side as a fiscal and not a political necessity, in other words a secular procedure devoid of any ceremonial value. The assessment and delivery of tax was carried out by Egyptian officials in the territory of the conquered land and only a small part of this reached Egypt (Panagiotopoulos 2000, 157, Fig. 1). But even this part was obviously not handed to the Pharaoh himself in his palace in the course of an official ceremony, but delivered in an ordinary, bureaucratic context. It was only the presentation of compulsory gifts from the vassals to their overlord which constituted a formal act of submission and required a ceremonial setting.[17]

One further iconographical feature which could be easily misinterpreted is the prostration in front of the Egyptian king by the men heading a procession. The fact that our scenes depicted a state ceremony strips this gesture of any particular historical significance. The purpose of the Egyptian artists was not to create an emblematic scene of political dominance in the tradition of ritualised motifs, such as the Pharaoh smiting foreign enemies with his mace (Schoske 1982), but rather to depict the ceremonial of the Egyptian court. There, every foreign emissary who came close to the Pharaoh had to kneel or prostrate in front of him. This formal act represented simply the obedience of the Egyptian court ritual but not necessarily a status of political subjugation (Bleiberg 1984, 159).

Third level: Historical Reality

We proceed now, after this critique of pictorial and written evidence, to the ‘heart of the matter’, the level of historical reality. At this final stage, the foreigners’ processions are to be set into their historical context. There are many theoretical models which could exploit the manifold significance of the depicted ceremonial episodes. One of these potential approaches, which seems to be very effective in its simplicity, derives from an observation by Norbert Elias in his book Die hofische Gesellschaft (1969, 129-130 n. 20). Elias noticed that every court ceremony embraces three functional levels, one primary and two secondary. The primary is (a) the original function of the event, in our case the actual delivery of gifts from foreigners to the Pharaoh. The two secondary comprise (b) the prestige function for the participants, here the importance of this ceremony for the high officials, and (c) the power/state function, here its importance for the Pharaoh and the state. Looking at the Egyptian court ceremonies through this three-fold prism we can make the following inferences.

First: The importance of diplomatic gift-giving in the Near East in cementing and advancing political relations between foreign countries is well demonstrated in the letters of the Amarna archive and has been the subject of analytical discussion (Zaccagnini 1973; 1983, esp. 198-227; 1987; Liverani 1990a, 255-266; Peltenburg 1991, 167-170; Cline 1995). This evidence implies that the most common form of a political relationship between two independent rulers at a parity level was an alliance of brotherhood. The manifestation of this bond of love and friendship was the exchange of valuable gifts bearing a personal character and a strong symbolic content. The question whether this form of exchange was primarily motivated by economic interests is of cardinal importance for the historical evaluation of this phenomenon and is therefore discussed in an appendix at the end of the paper. An equally high significance was ascribed to the gifts offered from subjugated countries to their overlord. They had, like the gifts of independent peoples, a prevailing symbolic meaning, thereby denoting not brotherhood but political submission and loyalty. [18]

Notable in this respect is that, in the case of Egypt, the gifts of the vassals seem to have occupied even greater importance than in other empires since the pharaonic state never used treaties in its political relations with foreign subjects. The princes or mayors of the conquered territories had to swear an oath of allegiance to the Pharaoh (Helck 1971, 246-247; Redford 1992, 198 n. 9). In this context, the regular delivery of gifts constituted, as a confirmation of the oath, one of the main obligations of the vassals alongside the payment of taxes.

Second: The significance of the ceremonies for the tomb owners has been outlined above. To make this point more explicit, it suffices to mention the evidence of some 18th Dynasty autobiographical texts which unveil a competitive struggle among the Egyptian high officials for prestige and status. The theatre for this competition was the royal court, where festivals and ceremonies functioned as social-integrative institutions. Every action at the centre of which the Pharaoh stood was invested with a special social meaning for all participants: the king turned it into a privilege by distinguishing those present from others. Proximity and accessibility to the king were the channels through which political prestige and power were distributed (Baines 1995, 133, 135). Some of the autobiographical inscriptions emphasise the rare privilege of approaching the king (Guksch 1994, 35-39, 119-138). The High Steward Amenhotep claims, for instance, on his Memphis stele:

“I entered the palace, (even) when it was out-of-bounds (to others) to see Horus (sc. the Pharaoh) in this his house, while (other) nobles proceeded out” (Guksch 1994, 37; for the translation Davies 1994, 8, 1794: 8-9).”

Henceforth, the foreigners’ processions depicting the official at the side of his king must have served essentially as a testimony of this rare privilege.

Third: The primary political significance of these audiences for the pharaonic state derived from the fact that Egyptians deliberately elevated the different political status of the gift-suppliers. As already noticed, the gifts of independent peoples were meant as a sign of friendship, whereas those of the dependent regions served as a sign of submission. While the Pharaoh could demand from his vassals the delivery of valuable objects as gifts, in the case of independent countries these gifts were of a voluntary nature and always required, according to the ethos of diplomatic gift-giving, counter-gifts of equal rank. Yet, the most striking feature at the level of pictorial representation is that both dependent and independent peoples were always rendered as having the same political status, even in cases where these emissaries appeared together. In the tomb of Useramun for instance, the independent Aegeans bring gifts together with the dependent Syro-Palestinians (Figure 1; Dziobek 1994, 91-92). A letter from the Amarna archive helps to confirm what we would otherwise suspect, namely that this lack of distinction was not an invention of the artists but reflected the common practice of the Egyptian court ceremonial. In this letter, the Babylonian king KadaSman-Enlil complained to the Pharaoh that during an official ceremony (probably a ceremonial parade in the Egyptian palace) the Egyptians put the Babylonian chariots not separately, but among those sent by the SyroPalestinian vassals (Moran 1992, EA 1: 88-98; Liverani 1990a, 265-266). The chance of a propagandistic exploitation of the gift-giving by independent countries, which always required a reciprocal offering, was given to the Pharaoh by virtue of the mechanisms of diplomatic giftgiving. According to this, the counter-gifts had to be offered not simultaneously but only on a later occasion, with an Egyptian embassy to the court of the foreign gift-giver. Through this practice the Egyptian king appeared in his land always as a receiver of foreign gifts and never as a supplier of these. The ideological concept demonstrated during these ceremonies to the Egyptian audience was that of the Pharaoh as a universal ruler who received contributions from all over the world (Liverani 1990a, 262). What the participants of the ceremonies could not see, and the later visitors to Useramun’s tomb did not know, was that the Pharaoh had the political and moral obligation, according to the existing diplomatic ethos, to reciprocate the Aegean gifts on a latter occasion with equally valuable offerings to the Aegean political centre.

It is possible to draw two conclusions from the threefold significance of these ceremonial events. The first supports again the historical authenticity of these pictures. Propaganda, as a deliberate manipulation of facts to make them fit the ideology, was definitely not the work of the artists. It was exercised at the level of historical reality and, as part of it, penetrated to the level of representation. The second conclusion is related to which of these three functions was more vital for Egyptian politics. Elias (1969, 130) noticed that in the French royal court of the ancient regime (17th-18th cent. AD), his field of research, the secondary function of these court ceremonies had been more important than their primary one. It seems very likely that in the pharaonic period as well the significance of these ceremonies for Egyptian society was deeply anchored in their secondary functions, for the officials involved and for the state, rather than in the action of the gift-giving itself. Therefore, these events’ ceremonial etiquette might have played a more essential role at the private and public levels than their actual content.

Conclusion

The examination of the Aegean processions within their systemic context implies that these scenes reflect rather than distort historical reality. To put it in a more explicit way, they constitute an accurate record of the manipulation of historical truth in the Egyptian court. Following the historical rehabilitation of this pictorial source, we can make some important inferences regarding both parties involved. From the Aegean perspective, these scenes are a document of political parity. The Aegeans appear as equal members of the international diplomatic community of the Near East, a community which used greeting gifts as a kind of a common symbolic currency to cement and advance both political and economic relations. From the Egyptian perspective, they serve as a document of political strategies. The foreigners’ processions became a favourite theme in the 18th Dynasty not out of an Egyptian ‘ethnographic’ interest in exotic lands but because the performance and, at a secondary stage, the depiction of these ceremonial events were embedded in the power structures of Egyptian society. At the most basic level of social interaction, the triangle Pharaoh, nobility and subjects, these ceremonies served the Egyptian king as a two-fold instrument of political power. On the one hand, he distributed through them favours of proximity to his officials and, on the other, demonstrated to the wider Egyptian audience that his power reached the limits of the habitable world.

APPENDIX

Royal gifts and their political vs. economic significance

The question of the alleged economic significance of diplomatic gift-giving exceeds the limits of the present subject in its strict sense. Yet, it plays a crucial role for understanding the essence of the depicted events and deserves therefore a deeper investigation.

There is a strong preference in current research to regard economic motives as the primary reason for royal gift exchange. In its radial version, this argument claims that royal trade is disguised as the exchange of diplomatic gifts or that ‘virtually all exchanges at the palatial level are recorded in terms of such reciprocal gift-giving’ (Cline 1995, 143; also Peltenburg 1991, 167-168 and Kilian 1993, 349).[19] More cautiously expressed, it stresses the fact that, in the Late Bronze Age, the exact boundary between royal trade and diplomatic gift-giving could not be clearly delineated (Warren 1995, 11). A letter from the Amarna archive, containing a very long list of valuable items, among them several thousand stone vessels, has been repeatedly cited to support the economic hypothesis (Cline 1994, 41; 1995, 143-144; Warren 1991, 298; 1995, 13). Should this huge amount represent in fact the habitual practice of royal gift-exchange, then this activity is to be regarded as a primarily economic phenomenon. Yet exactly the opposite is the case. This letter actually refers to an exceptional event. It comprises a list of precious objects which had been offered as gifts by Amenophis III to the Babylonian king, at the royal marriage of the first with the daughter of the latter (Moran 1992, EA 14). On such occasions large amounts of valuable goods were exchanged, either as dowry, or as a gift of the bridegroom to the father of the bride (Kiihne 1973, 23-39; Zaccagnini 1973, 30-32; Pintore 1978, 111-123; Artzi 1987, 25 with n. 15). There can be no doubt that dynastic marriages had, beyond their political/symbolic content, an enormous economic significance for both parties. But this practice diverges sharply from the regular gift-exchange among rulers. An examination of the entire corpus of the Amarna letters reveals that, in all cases of a normal gift delivery or exchange (about 25 in total), the amounts of the mobilised goods had always remained at a low level in terms of quantity. Let me illustrate by citing one of the smallest and one the biggest deliveries documented here.[20] To the first group belongs the letter from the Mitannian King TuSratta who sent as a gift to the Pharaoh one necklace made of lapis lazuli and gold (Moran 1992, EA 21: 33-41). One of the proportionally biggest gifts was sent by the same king to the Pharaoh and consisted of one gold goblet, two necklaces of gold and lapis lazuli, 10 teams of horses, 10 wooden chariots and 30 slaves (Moran 1992, EA 19: 80-85). All other deliveries in the Amarna archive fall within the same quantitative range. This evidence is corroborated by the data of the Annals of Tuthmosis III.[21] We observe here exactly the same pattern in terms of the nature and quantity of the items, featuring low figures of exotic raw materials or prestige objects with predominantly symbolic value. Furthermore, if we take the element of time into consideration, the economic insignificance of royal gift-giving becomes apparent. The seasonal patterning of the Amarna correspondence and the Annals of Tuthmosis III reveals that the exchange of gifts was in most cases a yearly procedure (Kiihne 1973, 120 with n. 605). We cannot even be sure that this always took place on a yearly basis. Symptomatic is the complaint of the Babylonian king KadaSman-Enlil to the Pharaoh:

“But now when I sent a messenger to you, you have detained him for six years, and you have sent me as my greeting-gift, the only thing in six years, 30 minas of gold that looked like silver” (Moran 1992, EA 3: 13-15).”

In light of this evidence, letter EA 14 cannot be used as an argument for the economic character of royal gift exchange since it refers, metaphorically speaking, to “an overdose (on the part of the scholars) of a type of document originally intended to be taken in small amounts over a long time”.[22] Both the Amarna letters and the Annals of Tuthmosis III imply that this activity was limited to a few valuables serving as a material token of a friendly relationship. An additional indication of the symbolic significance of this gift-giving is provided through the occasional exchange of identical products (Liverani 1979, 22-26). It is highly improbable that this channel of ceremonial gift-giving would have ever satisfied the demands of Late Bronze Age international trade.

It is tempting to take this observation one step further, beyond the monolithic evidence of purely numerical data, and try to draw a clear dividing line between gift exchange and royal trade in the written evidence. In so doing, we are facing a problem relating to the profane character of trade. Within the formality of official sources, the representation of this activity was marginal. In the Annals of Tuthmosis III there is no clear record of commercial transactions. In the Amarna letters as well, trade was not among the political issues discussed between rulers. But fortunately, we know of two examples, among 350 letters, documenting a commercial exchange. The implication of this evidence is that, in the Amarna archive, gift exchange and royal trade are not inextricably merged together but can be clearly separated in terms of phraseology and modus operandi. The first case is a letter from the Pharaoh to the ruler of the Palestinian city Gazru recording the exchange of some precious objects for 20 female slaves: “… Thus the king … He herewith sends to you Hanya, the stable [overseer] of the archers, along with everything for the acquisition of beautiful female cup bearers: silver, gold, linen garments: mal-al-ba-si, carnelian, all sorts of (precious) stones, an ebony chair; all alike, fine things. Total [value]: 160 deben (of silver). Total: 40 female cupbearers, 40 (shekels of) silver being the price of a female cupbearer” (Moran 1992, EA 369: 1-14).[23] This letter is unique in the Amarna correspondence for several reasons: (1) the detailed listing of both the commodities offered for exchange and the commodities to be purchased, (2) the citing of the exact value of these commodities in terms of silver, (3) the mention of the word ‘price’ (simu). It becomes apparent that, in this case, the Egyptian ruler is not exchanging greeting gifts but is involved in a commercial transaction.[24] The second letter, from the ruler of AlaSiya (Cyprus) to the Pharaoh, could be regarded as the most explicit evidence for the existence of two separate spheres for ceremonial and commercial exchange, respectively. In the first lines of this letter, the Cypriot ruler mentions his greeting gift to the Egyptian king:

“I herewith send to you 500 (shekels)[25] of copper. As my brother’s greeting gift I sent it to you” (Moran 1992, EA 35: 10-11).”

In the following lines, he requests some counter-gifts and then he complains to the Pharaoh regarding what seems to be a case of royal trade:

“Moreover, my brother, men of my country keep speaking with m[e] about my timber that the king of Egypt receives from me. My brother, [give me] the payment due” (Moran 1992, EA 35: 27-29).”

The word rimatu (‘payment due’),[26] etymologically related to the aforementioned simu, never appears among the other Amarna letters documenting a gift exchange and provides a clear indication of the commercial character of the activity. Furthermore, it is interesting to observe that this commercial transaction emerged at the level of royal correspondence only after becoming a political problem, as the words of the Cypriot ruler imply.

It is, in fact, difficult to reach absolute certainty in this matter. But, at the present stage of research, there seems to be no convincing evidence for applying a prevailing economic significance to diplomatic gift-giving. No doubt, a certain profit motivation can be traced in the letters from the Assyrian and Babylonian rulers who attempted to exchange gifts with their Egyptian counterparts in order to acquire gold from their partner. Yet, to consider this attitude as the primary reason for this activity would be misleading. It points rather to the gradual erosion of moral values in the ethical system of diplomatic gift-exchange. Only in this way can we explain the evident unwillingness of the Egyptian ruler to satisfy the demands or wishes of his partners.[27] From the other side, an indirect economic significance of royal gift-giving is undeniable, since this diplomatic activity advanced regular trade contacts between two foreign countries in providing the adequate political background.

In conclusion, it seems legitimate to distinguish between diplomatic gift-giving and international trade as two different spheres of exchange (Zaccagnini 1987, 57; Knapp 1991, 50; Sherratt & Sherratt 1991, 365). The first consisted of a mainly political activity well attested in the official sources, whereas the latter was governed by purely economic interests and because of its non-representative character left only scant traces in Near Eastern written and pictorial tradition.[28] The question whether this trade was fully controlled by the palaces or was partially left in the hands of independent merchants remains an equally significant issue but clearly goes beyond the scope of this paper.

Acknowledgements

I am especially indebted to Prof. Erika Feucht, who first introduced me to the iconography of the Theban private tombs and through the years continues to be a source of encouragement and invaluable assistance in Egyptological matters. I warmly thank Dr Susan Sherratt for a stimulating discussion, Dr Marika Zeimbeki for reading the final draft and making many insightful comments as well as Ulrike Krotscheck for improving the English. I am also grateful to Dr Andrew Sherratt for kindly encouraging me to publish this article in the Oxford Journal of Archaeology. – Prof. Dr. Diamantis Panagiotopoulos

Note: This research was originally published in the Oxford Journal of Archaeology 20, 2001, S. 263-283. It appears on Keftiu by permission from the author, Professor Diamantis Panagiotopoulos

Footnotes/Citations

- [1] For both terms see Vercoutter 1956, 33-123, 125-158; Sakellarakis 1984; Wachsmann 1987, 93-99; Haider 1988, 1-8; Osing 1992a, 273-280; Osing 1992b, 25-36; Cline 1994, 32; Helck 1995, 21-30.

- [2] All absolute dates in the present article follow von Beckerath’s chronology (1997, 189-190).

- [3] With an astonishing foresight the Egyptologist H. Brugsch (1858, 87-88) connected Keftiu with Crete almost a half century earlier; see also Hall 1901-02, 163 n. 1.

- [4] Some of the abundant literature on Aegeans in the Theban tombs has been recently collected by Rehak 1998, 40 n. 12.

- [5] The methodological danger of making historical inferences from iconographical data is well illustrated in the case of the palimpsest at Rekhmire’s tomb. There, the repainting of the codpieces of the Aegean emissaries as kilts had been erroneously associated with the shift of political power in the Aegean (see among others Schachermeyr 1960, 50-68 esp. 56; Helck 1995, 41^3) . This view was later discarded with convincing arguments (Sapouna-Sakellaraki 1971, 229; Rehak 1996; Rehak 1998, 42-45) .

- [6] Vercoutter (1956, 189-192) rejected, however, the historicity of the Aegean processions in the tombs of Menkheperresenb, Senenmut, Puimre and Amenemhab, by arguing that only the vizier could play an active role at the reception of foreign ‘tribute’. Contra Vercoutter, an examination of the iconographical evidence from a wider perspective (below) reveals that participation at these ceremonies was open for a wider range of high officials. Nevertheless, the viziers alone enjoyed the special privilege of substituting for the Pharaoh as recipients of the foreign offerings.

- [7] Porter, Moss and Burney 1970, 7T17 (7); 39 (5) (11) (12); 40 (2) (6) (7) (11); 42 (4) (5); 63 (9); 65 (2); 71 (3); 74 (11); 78 (8); 81 (5); 84 (5) (9); 85 (17); 86 (8); 89 (14) (15); 90 (9); 91 (3) (5); 100 (4); 118 (1); 119 (1); 127 (7); 131 (4) (11); 143 (6); 155 (3); 162 (1); 239 (2-3); 256 (3); 276 (3). The figures within brackets indicate register numbers of the mural decoration. For a discussion of foreigners’ processions see Wegner 1933, 58-64; Engelmann-von Carnap 1999, 254-257 and Shaheen 1988. A comprehensive treatment of the subject is still lacking.

- [8] In fact, each scene shows a compilation of only some of these elements which never appear all together. In nearly all cases the figure of the Pharaoh was in later periods intentionally deleted as a result of a damnatio memoriae.

- [9] An old coloured illustration from the Lepsius expedition, depicting the Syro-Palestinian procession from the tomb of Huy (7T40), provides the only example of a full arrangement of this scene type (reprinted in Davies and Gardiner 1926, pi. 19).

- [10] The scene in the tomb of Rekhmire is the most important and best preserved example of the whole group (Davies 1943, 17ff. pi. 17-23; Wachsmann 1987, pi. 40-^3).

- [11] Syro-Palestinians: TT 17 (7); 39 (12); 40 (11); 42 (4) (5); 63 (9); 74 (11); 78 (8); 81 (5); 84 (9); 85 (17); 86 (8); 89 (15); 90 (9); 91 (5); 100(4); 118 (1); 119 (1); 131 (11); 155 (3); 162(1); 239 (2-3); 256 (3); 276 (3); Nubians: 7T39 (5); 40 (2) (6); 63 (9); 65 (2); 78 (8); 81 (5); 84 (5); 89 (15); 91 (3); 100 (4); Punt: 7T39 (11); 89 (14); 100 (4); 143 (6); Hittites: TT 86 (8); 91 (5); Mitanni 91 (5). This compilation does not fully coincide with the catalogue of Porter, Moss and Burney (1970, 464, Appendix A, 5), since the latter includes depictions of foreigners in various iconographical themes.

- [12] For some isolated examples from earlier periods see Vercoutter 1956, 185 n. 1.

- [13] The foreigners’ processions never became a favourite theme in the mural decoration of temples or other public/ representative buildings which was dominated by pictures of ‘symbolic conquest’. To the few examples mentioned at LA VI, 766 no. 2 one can now add a gateway relief from the Karnak temple dating to the reign of Amenophis I (Redford 1979), two talatat from the same site (Redford 1988, 15 pi. 7:2; 7:4) as well as some very fragmentary wall paintings decorating a ceremonial building of Amenophis III in Kom al-Samak at Malqata South (Nagasaki 1998, 25-26; I am grateful to Takao Kikuchi for calling this recent finding to my attention) Regarding their mode of representation and symbolic connotations, these examples are clearly different from their sepulchral counterparts at Thebes. For instance, on the gateway relief from Karnak the offering-bearers are not emissaries but personifications of Asian places, a clear indication of the non-realistic, symbolic character of the scene.

- [14] A. Persson (1942, 145) was the first who alerted the attention of Aegean archaeologists to the etymology of the word as ‘that which is brought’; see later also Str0m 1984, 193.

- [15] Vercoutter (1956, 131, 133) had on some occasions proposed alongside the traditional translation ‘tribute’ an alternative meaning as ‘cadeaux’. See more recently Cline 1995, 146 n. 21 (following Schulman 1988, 73 n. 55). For a detailed discussion of the term with additional bibliography see Panagiotopoulos 2000, 149-150.

- [16] or the chronological relation between the foreigners’ processions and both written sources see Figure 3.

- [17] Nevertheless, there are a few isolated examples, depicting emissaries from subjugated countries only, which obviously refer to the delivery of tribute. These scenes can clearly by distinguished from our main body of evidence, since they do not display an ceremonial character: the Pharaoh is absent, the prostration is generally omitted and the items brought consist exclusively of agro-pastoral products or raw materials, see for instance Porter, Moss and Burney 1970, 7T40 (2).

- [18] For the ethical and political codex determining the giving of compulsory gifts see Zaccagnini 1973, 170-179. The subtle, yet crucial difference between tribute and compulsory gift was stressed by Finley (1977, 96) "… a gift to a ruler, even when compulsory for all practical purposes, is in its formal voluntarism of another order from the fixed tax with its openly coercive character".

- [19] The origins of this line of argument can be traced back to the pioneering article of A. Keramopoullos (1930, 3940) on the industrial and trade activities of the Mycenaean ruler at the palace of Thebes. His arguments were later elaborated by S. Alexiou (1953-54, esp. 137, 139; 1987, 152-153).

- [20] This evaluation relies purely on quantitative criteria, since the actual prices of individual items cannot be estimated with confidence.

- [21] Urk. IV, 647-734; translated by Blumenthal et al. 1984, 188-223. The long lists of gifts (jnw) coming from Syro-Palestine represent total amounts from the region, obviously consisting of numerous individual deliveries from the cities under Egyptian political control (Panagiotopoulos 2000, 149 with n. 121).

- [22] With apologies to Liverani 1990b, 348.

- [23] For this letter see also Liverani 1979, 32. One Egyptian deben (c. 91 g) equals approximately 10 shekels (1 shekel = c. 9g).

- [24] Zaccagnini emphasises the absence of ‘money’ and ‘price’ from ceremonial gift-exchange: "Gifts should be reciprocated only by counter-gifts … A gift ought not to be ‘paid’, i.e. reciprocated with ‘money’ … To repay a gift with a neutral (i.e. impersonal, fungible) means of payment — whatever its nature — not only bespeaks a clear case of ‘conversion’, but debases the ceremonial level o

- [25] This unit of measure is not cited in the letter. The word shekel is however a more plausible emendation than minas or talents, since the Cypriot ruler apologies for the small quantity of his delivery (Moran 1992, EA 35: 1215).

- [26] The most common meaning of slmatu is ‘purchase, property acquired by purchase’, see CAD, vol. 17 s part III, 2. In our case, however, the translation ‘payment due’ (Moran 1992, 107 with n. 7) is dictated by the word s context.

- [27] This unwillingness is documented either as a direct, unequivocal statement of the Pharaoh, or else as an indirect indication of its occurrence, i.e. through the frequent complaints of his unsatisfied Near Eastern partners. For the case of gold in the royal gift-exchange and its negative aspects see Zaccagnini 1987, 59.

- [28] It must be finally underlined that the classification of a social phenomenon into a modern analytical category (for instance political or economic) is purely conventional. By describing in our case the diplomatic gift-giving as a political activity we are trying to comprehend the main essence of this social interaction, not the full range of its possible historical manifestations.