By the time artisans finished decorating the inside of the tomb of the Egyptian vizier Rekhmire, only a pale reflection of the greatness of the people known as the Keftiu remained. The carvings and paintings dedicated to the 18th Dynasty noble associated with Thutmosis III and Amenhotep II told of gifts from afar, one hundred years after the Thera cataclysm ended the world’s first Thalassocracy. The enigmatic people deemed “Minoan” by Sir Arthur Evans, became a footnote in history by 1400 BCE. All that remains, so far, are the ripples in time these enigmatic people left. What if the explanation were the simplest one?

Forgotten for thousands of years, were the traces archaeologists research and toil to unearth and classify these days. Until Evans, all the world knew of the remarkable Keftiu empire were stories passed down orally from the people of the region. As astonishing as this sounds, it wasn’t until Evans began investigating these tales and clues he found studying the Mycenaeans that any hint of one of humanity’s great civilizations was witnessed. Now, we have unbelievable palace temples, treasure troves of miraculous artifacts, and better clues as to who these fascinating people were. Besides being Keftiu, these ancient people might also have been referred to as the Caphtorim, or people even those people associated with the Akkadian term Kaptara.

Still, we are in the dark about connecting these Keftiu on a timeline or putting together big pieces of the historic puzzle they represent. No one knows for sure what exactly became of the Keftiu (Minoans). We only have a kaleidoscopic view of their rich culture, fragments of their language, most still undeciphered (Phaestos Disc above), and theories about almost every facet of their existence. As the renowned archaeologist, Diamantis Panagiotopoulos wrote in his paper, “Keftiu in Context: Theban Tomb-Paintings As a Historical Source”:

“One century has now elapsed since the identification of Keftiu with Cretans and at first glance, after this long period of intensive research, there seems to be little hope of contributing any original ideas on the subject.”

And the absence of reference to Keftiu makes things more interesting. Of course, there is no mention of the term “Minoan”, since this term was a construct of Evans. So, Keftiu as a people and as a civilization being obscure from our histories is intriguing, to say the least. Even if Cretan Hieroglyphs, Linear A, and other iconography were to be deciphered, only a corner of the monumental puzzle would be put in place. The following from Evangelos Kyriakidis via “Indications On the Nature of the Language of the Keftiw From Egyptian Sources” adds credence to the Keftiu being Minoans from Crete:

“Of all the Cretan names the only one which is very easily recognisable is the twice repeated ‘am(a,l)-ni- f(a,u). Its striking similarity with the modern ‘Amnissos’ and with the Linear B a-mi-ni-so is conclusive, though its repetition in the same text is puzzling. Several notes have to be made on this. The association of the name of Keftiu with a port site so close to Knossos, the largest Cretan city, renders the association of Keftiu with central Crete very likely indeed.”

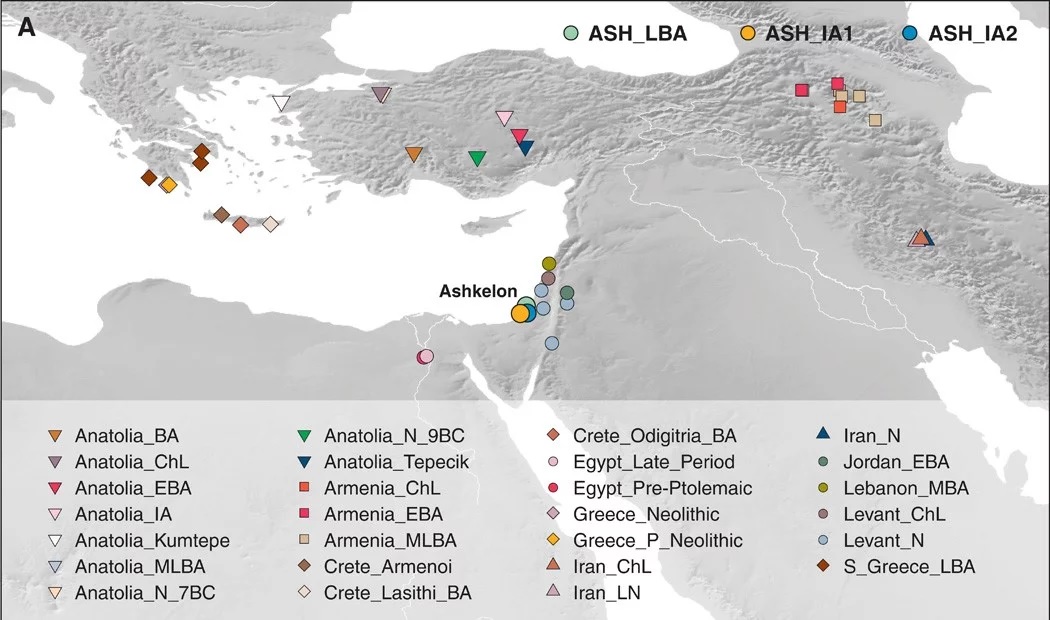

The best minds in the field of Aegean prehistory cannot even agree on the substantive evidence from most of the artefacts already unearthed. On chronology and Bronze Age ceramic style, etc., there is agreement. But critical pieces like the famous Phaistos Disc and other seemingly critical pieces create more questions than answers. Who the Keftiu really were remains as puzzling a question as it was before Evans, in most instances. Could these be the people associated as the bodyguards of King David? Were the Keftiu the ancestors of the Philistines (see this DNA study)? And, were the Cherethites who protected the King who possessed the sacred Ark from the line indicated in the aforementioned study from Crete? The name mentioned in Ezekiel 25:16 and Zephaniah 2:5 translates to “Cretans” according to some scholars. (See James E. Jennings) Along these lines of inquiry, we find sensational and fascinating associations from biblical references.

For instance, in 1922, when Howard Carter opened the tomb of Tutankhamun in the Valley of the Kings, one of the most amazing artefacts was a processional ark, listed as Shrine 261, as the Anubis Shrine (above). On the news of the discovery, some in the archaeological community said that the Anubis Shrine could, in fact, be the long-lost Ark of the Covenant. The similarity of the chest on which the Egyptian god sat with that of the famous ark is striking indeed. There are many such “loose” parallels that scholars and enthusiasts mull over to this day. But science is about what can be proven, even if speculation often leads to fact.

Not long ago, I was visiting the renowned archaeologist Dr. Jan Driessen at the Sissi Archaeological Project. The discoverer of yet another Minoan palace/temple site is one of the most cited experts in the world on these subjects. At length, I asked him about the number of Sissi-like sites that might exist on Crete undiscovered. His answer startled me, even though I already suspected. “There could be a hundred, perhaps more,” the director of the Belgian School at Athens said. This affirms, at least numerically, assertions from Homer’s Odyssey. (Pearlman – U. Chicago Press)

“Yet even so will I tell thee what thou dost ask and enquire. There is a land called Crete, in the midst of the wine-dark sea, a fair, rich land, begirt with water, and therein are many men, past counting, and ninety cities.” – Homer, The Odyssey

Driessen, along with Athanasia Kanta, Kostis Christakis, the curator at Knossos, the aforementioned Dr. Panagiotopoulos, and a score of other archaeologists working here in Crete, are the gatekeepers of what is currently known of the Keftiu. Most of the archaeologists I speak with have no problem with identifying the “Keftiu” of Egypt mentioned with Evans’ Minoans, but it’s also true that there is virtually no physical evidence beyond scattered fragments. Biblical connections, all the conjecture about lost Atlantis, metaphysical supposition, and a nebula of possibilities surround fundamental questions as to who we are and where we came from. At least in a Neolithic, prehistoric, Bronze Age context. And, on their somewhat stoic adherence to scientific principles, I wholeheartedly agree with them. We would be nowhere without their diligence and adherence to procedure and good form. But I am not an archaeologist. And, the stories that have led to so many discoveries are what interest me almost as much as the hard evidence residing in places like the magnificent Heraklion Archaeological Museum (go there if you can).

These Keftiu, if I may, were unbelievably refined, intelligent, and artistic, not to mention powerful during their time. I refer to them, like other authors, as the first thalassocracy, to which none of the experts so far have disagreed. This theory is the simplest and most logical explanation for the Keftiu/Minoan Utopia some describe. Still, the extent and nature of their maritime empire is as in question as any other facet of their existence. The greatest minds in the field only assume the nature and power of Knossos, for instance. Other sites like Phaistos and Zakros, even Galatas, Malia, and Sissi as well, remain as the life’s work to be done by the Driessens of archaeology. And we must admire them all for this uncommon dedication. But we must also push, as humanity, to help them uncover and preserve more of this glorious past. For within the undiscovered palace or tomb somewhere on Crete, we may find the Rosetta Stone of these Keftiu, or for all we know, that remnant of the Ark Hollywood films tease us with.

Finally, beyond the scattered evidence, or in the tombs of Senenmut, Useramun, Menkheperresenebm, or Rekhmire, it is intriguing to consider there is no other definitive mention of the Keftiu. And on the subject of the first thalassocracy, several experts have dissenting views. I would contend, however, that their vision, logic, and contextual senses are off by a wide gulf. Whatever else we know of Keftiu, it sure that these people thrived (somehow) in unfortified cities smack in the middle of a barbaric world. And for not hundreds but over a thousand years. Unless they were beneficiaries of some blessings of Poseidon, or Atlantean technologies, then we must certainly consider their prowess at sea as a factor.

I believe that a partial explanation for the relative lack of iconography concerning the Keftiu may be found by looking at how the Egyptians seemed to envision and deal with artistically these fascinating people. Look at the so-called “hybridised” Keftiu/Syrian figures in tombs were inefficiencies by Egyptian artists, according to Dr. Panagiotopoulos. These images were only used to convey how the Keftiu appeared in the collective mind of the people under the pharaohs. In my opinion, he is right because this would explain to a great extent why there is so little earlier evidence of the Keftiu in other tombs. Still, the archaeologists caution me that relative to the Keftiu, the Egyptians did not generally focus on other cultures and states. So, the depictions and records of these people existing at all seem to attest to their importance. If I may explain, perhaps the significance of the Keftiu can be framed more aptly.

Aegean figures were often associated with lands to the north of Egypt, in much the same way Nubian figures came to represent the regions to the south. (See Uroš Matić) Both Syria and Keftiu came to represent what lay north of the realm of Pharoah. And for Ketiu, it seems clear from all the scant evidence that the ancients considered the Keftiu (Minoans) as the gatekeepers of the unknown that lay outside Egypt’s grasp. So, what if Ketiu itself was a true mystery, a place inaccessible altogether, except by the power of Keftiu thalassocracy? This would explain a lot. Maybe Crete was just that inaccessible in the time before written history, and the Keftiu decided who and what came and went. This is a novel but new and fascinating idea (insert due humility here). I suppose it’s possible that the level of control and access these Keftiu had could have been so supreme that very little would have been known of them before the Mycaneans. That is, except for their supremacy and gifts.

Gifts from Keftiu. Fragrant oils, unimaginable textiles, incomparable ceramics and art were all guarded and exclusive to the extent that their desirability was super-enhanced! What would a local merchant think on the day a state-of-the-art ship from Amnissos or Kommos arrived in port? Would ancient customers scramble to be the first to see the colourful delicacy found nowhere else? And treasures ferried to their shores aboard the first vessels to truly harness the wind blown by the gods! Ah. You see, I digress. Driessen and the other scientists will frown but do what they do best: weigh every molecule of evidence and reweigh it. And we must help them to find the Keftiu in whatever ways we can. That is if we truly want to know who we are, what we became, and what we could be. A rebirth of Keftiu? Perhaps.

Publisher’s note: This paper was originally published on Argophilia Travel News

Photo credits: The Griffin fresco image – courtesy author, researcher, and historian Mark Cartwright